Studio Visit with Jo Nagasaka

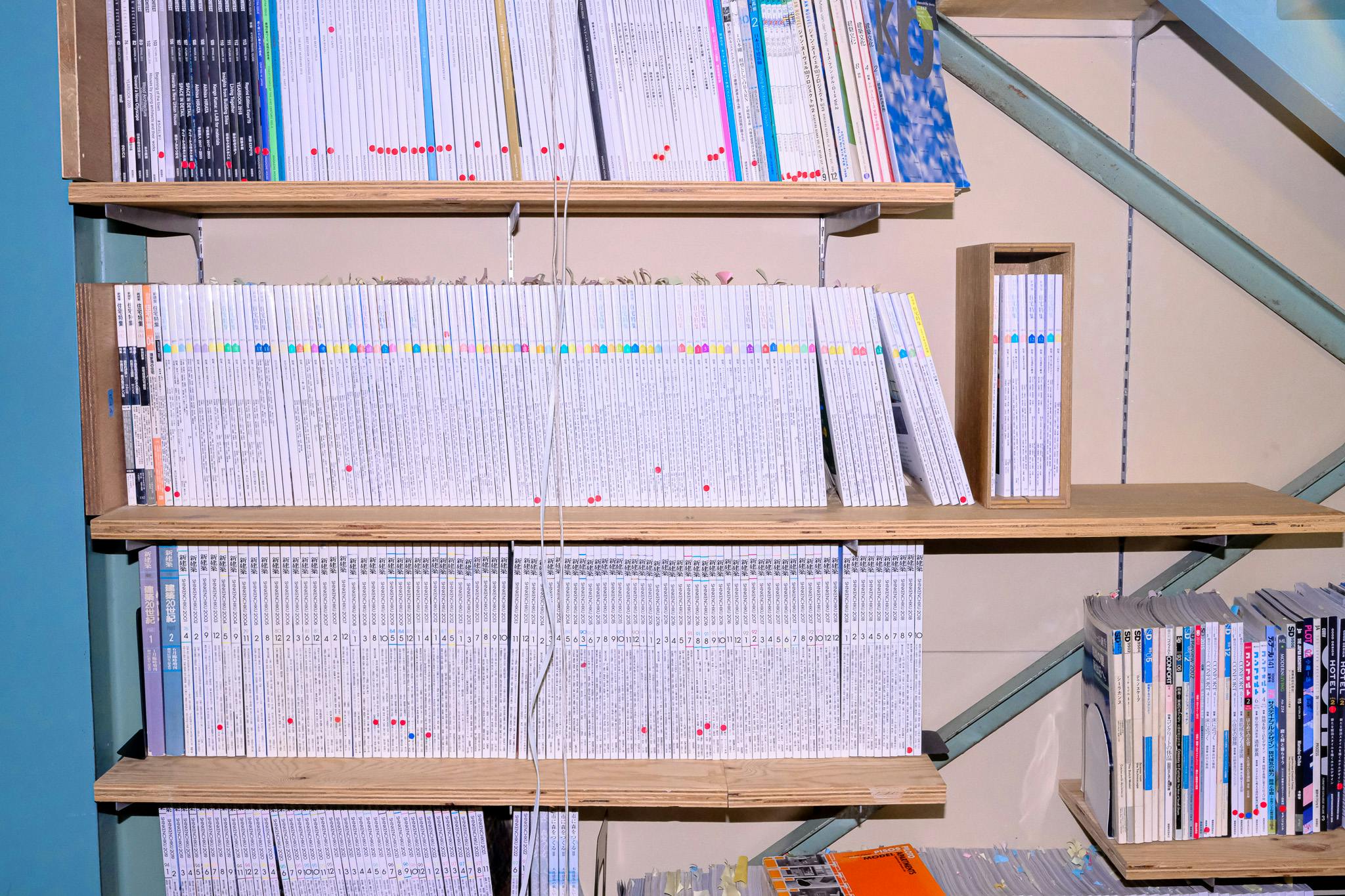

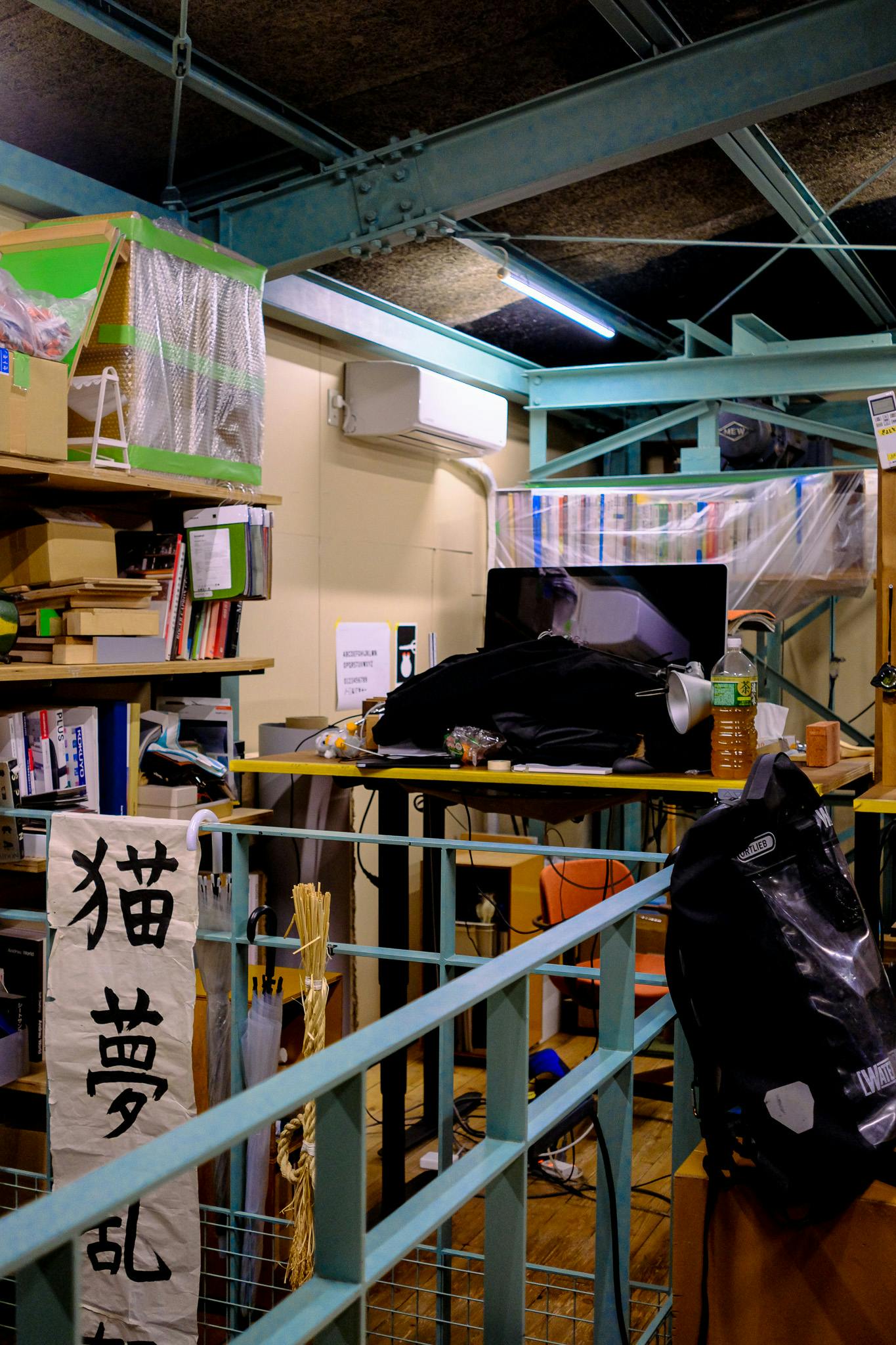

We visit the Sendagaya Studio of Tokyo-Based Architect Jo Nagasaka of Schemata Architects

Tokyo-based architect and designer Jo Nagasaka trail-blazed his unique architectural career trajectory by levelling up, so to speak, in the video game of career-building by meeting restrictive budgets with extreme creative flexibility and malleability, using new technology to advance in sustainable solutions for the local Japanese issue regulations around reusing architectural materials.

Kristen de La Vallière_ I've been a fan of your work for a long time; you were actually the first designer I contacted to interview when I started say hi to_ in 2015. I just wanted to start by asking if you could introduce yourself and your studio.

クリステン・デ・ラ・ヴァリエール_ 実はずっと前から長坂さんのファンです。2015年にsay hi to_を立ち上げてから初めてインタビューを依頼させていただいたのも長坂さんなので、このような機会をいただきとても光栄です。まず初めに、ご自身とスタジオについてご紹介いただけますか?

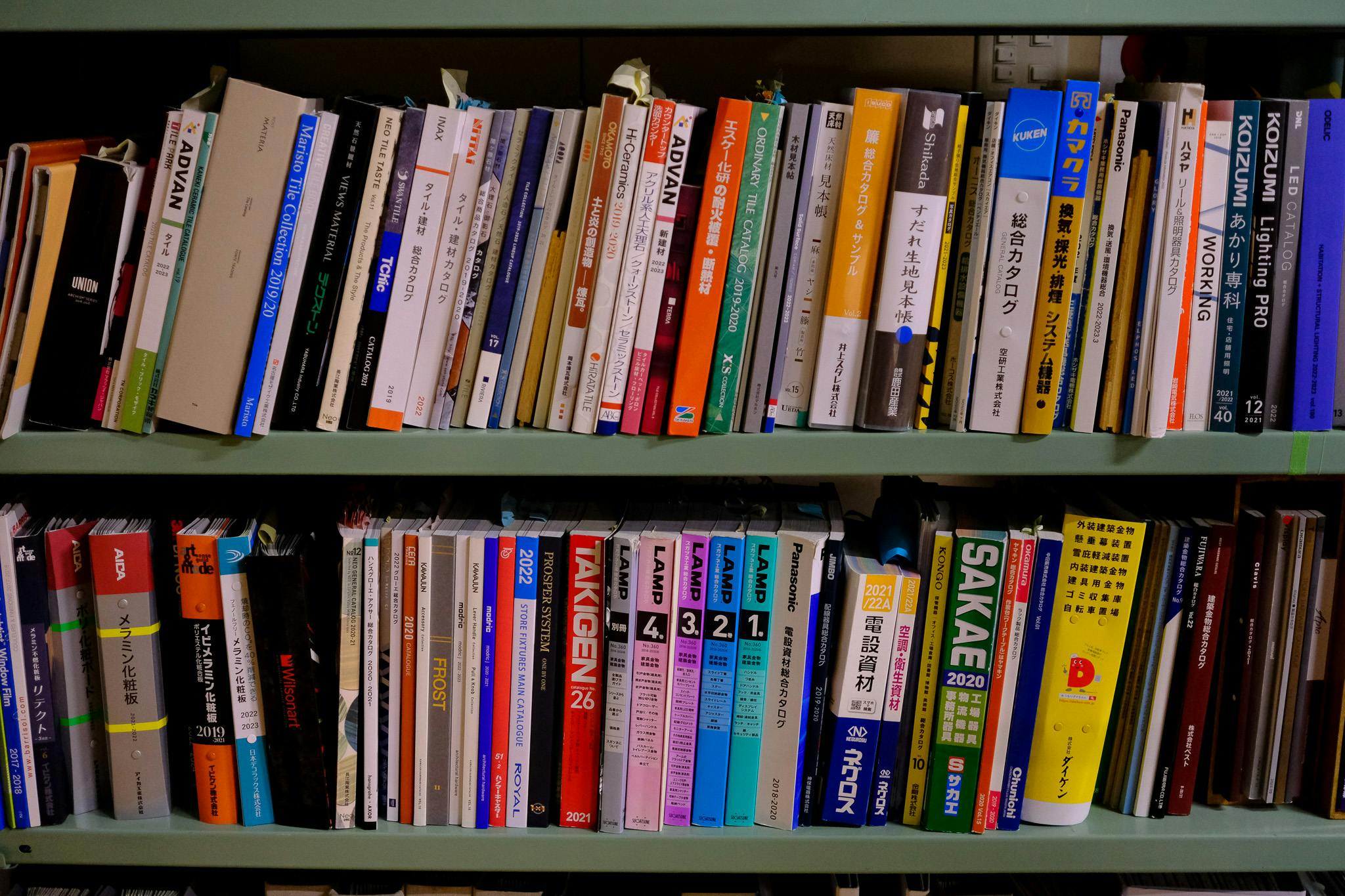

Jo Nagasaka_ I graduated from University 25 years ago in 1998 and started my own studio, Schemata Architects. I started with furniture gradually, then progressed to interiors and architecture. We are currently designing various architectural projects, interiors, furniture, houses, shops, hospitals, and public bathhouses (sento). Generally, when companies scale up, they stop making small things, but we still design furniture.

The most important thing in design is the "renewal of knowledge." We explore what triggers design by gaining learning new things and re-recognition for things that are taken for granted. For instance, in the case of my product Flat Table(2008), the piece which you first fell in love with in 2015, if you pour the same color over the bumpy areas, the deeper areas will become darker, and the shallower areas will become more transparent. This work was born from the recognition of this phenomenon.

長坂 常_ 1998年に大学を卒業してそのまま事務所であるスキーマ建築計画を立ち上げ、もう25年になります。最初は家具から少しずつ始めて、インテリア、建築と進めてきました。現在は住宅やお店、病院、お風呂など、様々な建築やインテリア、家具などの設計を行っています。一般的に建築家は、スケールアップをすると小さいものづくりをしなくなるんですけど、僕たちは今も家具デザインを行っています。

デザインにおいて1番大事にしているのは「知の更新」。新しい知識を得ることや、当たり前のことを再び認識することで、デザインのきっかけとなるものを探っていきます。例えば最初にクリステンが好きになってくれた僕のプロダクトであるFlat Table(2008)でいうと、でこぼこだったところに、同じ色を流したら、深いところは濃くなって、浅くなと透明に近づくっていうことを改めて、ちゃんと認識すると、それがデザインに変わって生まれたのがあのFlat Tableなんです。

So you're kind of experimenting first sometimes with the material.

つまり実験をすることから始め、その対象が時にマテリアルになるということでしょうか?

Not only materials but also discoveries from conversations can lead to new designs.

DOMAE DENTAL HOME CLINIC (2022) would be a good example. The client was a dentist with a "holistic medical care philosophy." The brief to us was to express "medical care that provides comprehensive prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for each individual" through the design. I wasn’t familiar with such a concept up until then, so I started the project by asking the client to take us to various dentists to understand properly.

However, I discovered that some dentists do not fit these stereotypes. I noticed that the patients [in the sample dentist office] seemed comfortable and felt they were treated properly and fairly. If there is no wall between you and the patient next to you, you will understand that there is nothing to hide and everyone is treated fairly.

This project was created by learning about our client's approach to their trade, dentistry in this case, and how we could apply those new discoveries about our client's approach into our spatial design for them. I believe it is important to "renewal of knowledge" in many elements, such as conversations and materials, to develop new ideas.

マテリアルだけでなく、会話の中からも発見したことが新しいデザインを生み出すこともあります。

例えば、歯科兼住居の設計プロジェクトである堂前さんちの歯医者さん(2022)。クライアントは「全人的医療」を理念とする歯医者さんでした。個々人に合った総合的な予防や診断・治療を行う医療を、歯科の建築を通じて表現したいという要望内容でしたが、それまでの僕はそのような概念を知らなかった。なので、まずはちゃんと理解するためにいろんな歯科へ連れてってもらいました。

僕が最初にイメージした一般的な歯医者って、囲われた密室で治療されて、高い歯を買わされてっていうのが当たり前で、自分が適切な治療を受けているのかどうかはブラックボックスのようにわからない空間でした。

でもそうでなくて、オープンな歯医者があるということを知ったんです。このイメージに近い他の歯科の現場を見にいくと、ちゃんと公正に治療されてる感じが出るんだということに気がつきました。隣で治療されている人の話が聞こえてきて、みんな違うそれぞれの治療方法を横で感じられる方が、自分もどういう判断で治療をされているか納得感が出るんです。そんな新しい歯科の形を会話の中で知ることができ、その発見を空間にどう落としたらいいかってことを考えて出来上がったのがこのプロジェクトです。会話やマテリアルなど、多くの要素の中で「知の更新」をしていくことが、新しいアイデアを展開していくために重要なことだと思っています。

Your approach is very conceptual and can lead to better outcomes for how the space is used in new ways. I imagine not all clients are so open-minded, and it can be difficult to convince the client of your new approach. How do you deal with that?

あなたのアプローチはとてもコンセプチュアルで、他にない新しいアウトプットが大きな価値を生み出していると感じます。想像するに、時にクライアントに対してあなたの新しいアイデアを理解してもらうのに難しい時もあるのではないかと。

I assume many of our clients are asking us to work together because they’d like to have something unique, so we don't have difficulties persuading them. Basically, when clients give us requests, they already understand our work concept. So I feel like many clients are looking forward to seeing how we will come up with a novel and unexpected suggestion and proposal.

すこし変わったものが好きな人が僕たちに頼んでくれるので、説得することに困ったことはあまりないです。基本的にクライアントの方々が依頼をくれる時には、僕たちのコンセプトをすでに理解してくれている。なので僕たちがどうやって答えを出すのか、楽しみに待ってくれている人の方が多い気がします。

It must have been difficult at the beginning before you had a portfolio for potential clients to know of and trust your vision and creativity. How did you get your first job?

独立後の当初、ポートフォリオを制作する前にあなた自身のビジョンや創造性に対する信頼を、潜在顧客から獲得していくのは大変だったのではないでしょうか?どのように最初の仕事を掴んだのですか?

I started with small pieces that I could make myself, so making a portfolio wasn't that difficult. First, I made furniture requested by a friend, and people who saw that furniture asked me for another one, and people who saw it asked for interior design. By doing so, I could build a portfolio.

最初は自分で作れるような小さい規模のものから作り始めたので、ポートフォリオを作り上げることはそれほど難しいことではなかったかな。 友人から頼まれた家具を作って、 その家具を見た人がまた家具を頼んでくれて、それを見た人が次はインテリアを頼んでくれて。そんな流れのなかで、ポートフォリオが徐々に作られていきました。

How did you think that you have established such a notable position in the architecture world to be able to have clients come to you for your vision? I think that is the dream of many architects.

長坂さんのデザインを求めている方がたくさんいて、建築の世界で注目される地位を確立されました。多くの建築家の夢だと思いますが、ご自身はどのように感じられていますか?

Perhaps I was able to find it because I hadn't become an architect with the same goal that many other people who aspire to be architects have. For example, ever since I was a student, I never dreamed to make something “big,” like a hall or a museum. Instead, what I pursued was how to design while talking with people and saying, "wow, that's interesting!". The starting point is very different, so with this approach, I was able to find my niche and develop my own path.

建築を志す大半の人たちと同じような衝動から、建築家になってないから自分のポジションが得られたのかもしれません。例えばホールやミュージアムみたいな「大きなものを作りたい」とか、「住宅を作りたい」とか、学生の時から全く思ったことがなかった。そうではなくて、先ほどの例のように、クライアントや仲間との会話の中で「それ面白いですね!」って言いながら、どう形にしていくかが僕の1番やりたいことです。その出発点が大きく違うから特殊なポジションなのかなと思います。

Where did you define this path or philosophy to your practice?

ご自身の方針やフィロソフィーについて、どのような経験から現在のスタイルへと落とし込んだのでしょうか?

The project of Sayama Flat (2008), ten years after I started my office, was a turning point for me.

When the renovation of Sayama Flat was finished, I went to see how it was after a while. I saw that the people who lived there had made various changes and added a sense of life to it. When I saw each room, I found the paintings and decorations had transformed the space I had designed into something I had not expected. I thought it was natural and good, and it was simply fun to see.

Until then, I didn't like the fact that the building I designed was just covered with laundry. However, I started to pursue a design that has strength and rigidity.

To tell the truth, for the first ten years of my design career, I was really worried until I was convinced that my position was this. There were many architects with strong concepts and identities in the generation above me, so I felt a sense of duty and pressure to have a personality and way of thinking that would rival them. Altough when I had this epiphany at Sayama Flat, I felt like I should just do what I could, and at that time, I was able to work with my own concept.

After that, we steadily continued house renovations, such as House in Okusawa (2009). HANARE (2011) was designed as the first building to embody this new philosophy and approach. In the process of having to design from scratch like a new building, I was able to realise what I am and what I am interested in because of my experience. It has become a fully integrated project.

僕にとってはかなり大きな出来事は、事務所をはじめてからちょうど10年経った時のSayama Flat(2008)でした。

Sayama Flatのリノベーションが完成して少し経ってから様子を見にいくと、そこで暮らす人が色々手加えたりして生活感が出てきているのを見ました。それぞれの部屋に行ってみたら、思いもよらない色が床に塗られていたり、壁の姿も変わっちゃっていたり。それが自然でいいなって思ったし、単純に楽しそうだなって思ったんです。

それまでの僕は設計した建築に洗濯物がかかってるだけで本当に嫌なくらいだったのですが、Sayama Flatをきっかけに誰かの手が加えられていってもへこたれない、強度のあるへっちゃらなものを作りたいと強く思うようになりました。

実はそれまでの10年間、自分のポジションに対してすごく悩んでいたんです。近い世代にはコンセプトの強い建築家がたくさんいたので、彼らに負けない個性や考え方を持たなければならないという義務感やプレッシャーを強く感じていました。でもSayama Flatでの発見をきっかけに、「自分のやれることをやればいいや」みたいに吹っ切れて、それからは自分のコンセプトで仕事ができるようになりました。

その後に奥沢の家(2009)などのリノベーションを着実に続けて、その流れの中で初めての新築としてHANARE(2011)が実現しました。新築のように1から設計していかなければならない過程において、それまでの経験を経たからこそ気づくことのできた、「自分とは何か」「何が自分の興味なのか」っていうことを具現化したプロジェクトになりました。

I read that a lot of the houses in Japan are not built to last a long time. Can you explain the Japanese approach to architecture and why houses are often demolished and rebuilt?

日本の建築の多くは、西洋に比べて短期間ですぐ解体されてしまうという話を聞きました。日本における建築のアプローチの特徴と、なぜ解体しては建て直すということが頻繁に繰り返されているのか教えていただけますか?

One of the reasons would be that our architecture is mainly made of wood which gradually falls apart and is sadly easily flammable. Another reason can be due to the frequency of earthquakes in Japan. Since Postwar, Japan has continually updated its laws and safety-building regulations to protect structures from natural disasters. Every time the rules change, we need to submit a confirmation application to the government, and if it does not conform, we will have to rebuild it. If you constantly preserve and update the building to conform to new safety measures, the costs quickly add up, so in most cases, it is less expensive to demolish and rebuild.

For some reason, the Japanese financial industry is also involved. They spend a lot of money on new buildings but don't lend money to purchase or preserve old buildings. There may be a lot of political work in this country as well. Japan's economic base has a fairly large proportion of it’s GDP in civil engineering. The building laws change every five years. In the public face, it is for ensuring safety against this natural disaster, but I feel like it's a mechanism to create new buildings to keep the economy running.

原因の1つは木造の建物が多いことですかね。だんだん痛んでいったり火事が起きやすいっていうのが大きな特徴です。もう1つは、やはり地震が頻発することも大きな原因でしょう。地震が起きるごとに、安全性を守るために法律がどんどん改正されるということを、戦後の日本ではずっと続けられています。そして法改正の度に確認申請を役所に出して、不適合の場合は建て替えなきゃいけなくなってしまう。手をかけて保存すると費用がかさんでしまうので、壊してしまった方がコストがかからない場合がほとんどです。

なぜか日本の金融業界の性格も絡んでいて、新しい建物にはものすごくお金をかけますが、 古い建物に関してはお金を借りるのが難しいです。ひょっとしたら、この国の政治的な働きも多いのではないかなと推測します。日本の経済基盤は、土木や建築の割合がかなり大きいです。5年ごとに建築法が変わるけど、この災害に対する安全性の確保という盾をうまい具合に使いながら、経済を回すための仕組みになってるような気も。

I was also reading that you love working with the latest technology and reclaimed material and that you had done a project scanning pieces of houses that you can rebuild. What is that project?

長坂さんは最新のテクノロジーや再生素材も積極的に使われて、家の部材をスキャンして新しい建物を再建したプロジェクトも行われています。このプロジェクトについても是非教えてください。

For example, when looking at the town of Kyoto, let's say that there is a piece of wood that you think is wonderful among the scraps of demolished buildings. However, according to Japanese law, recycling waste materials may not be suitable for structures as per safety laws. It is difficult to control if the material standards are not fixed, so it was normal to handle the material within the standard. There was a material with a special shape, and no matter how beautiful it was, it was not treated as non-standard.

When managing waste materials, it is difficult to manage as it is necessary to keep track of data such as size, strength, and condition - for each piece of scrap material. Therefore, to we have no choice but to throw it away.

But now, with the advancement of computer technology, we have entered an era where information can be easily managed even for non-standard materials with unique characteristics. The scanned material data is imported into CAD, classified into small segments, and stored. The time will soon come when it will be common to reuse things as part of design.

At the Venice Biennale 2020, we exhibited this experimental approach. We scanned each part created in an old demolished building in Japan and displayed it. It was an attempt to get a hand there and make something else. In Oslo, there is actually a building that utilizes the old material from the demolished Japanese structure in a new building.

例えば京都の街を見ると、解体された建物の廃材のなかに、素敵だなと思う木があったとします。でも日本の法律上、廃材の再利用は、特に構造物においては不適合になってしまうことがあります。なぜならば材料の規格が一定でないと品質をコントロールしにくいので、規格の中で材料を選ぶのが普通でした。なので特殊な形状をした材料があって、それがどんなに美しくても、規格外だと取り扱われなかったんです。

でも今はコンピューター技術があって、規格外の個性を持った材料でも情報管理が簡単にできるような時代になってきました。材料のスキャンデータをCADに取り込み、細かいセグメントに分類して保管しておく。そしてデザインの一部として再利用するっていうことが、一般的にできる時代がもうすぐ来ると思います。

その実験的なアプローチとして展示したのがベネチアビエンナーレ2020。解体された古い建物で生まれた1つ1つのパーツをスキャンして、それを展示する。そこへもらい手が来て、何か他のものを作るという試みでした。オスロでは実際に、その材料を新築で活用した建築があります。

WecollectedwastematerialsinKyoto,processedthemtosomeextent,transportedthemtoNewYork,andassembledthemtherewithaJapaneseconstructioncompany. InKyoto,thesewastematerialsarejustgarbage,butifyoubringthemtoNewYork,theyareprizedandcherishedandsurprisinglygoodvalueformoney.

Jo Nagasaka

What have you been exploring in some of your more recent projects?

直近で取り組まれているプロジェクトには、どのようなものがありますか?

In the summer of 2022, we opened a store, 50 Norman in Brooklyn, New York, where we used waste materials from the demolition of a house in Kyoto. I thought it would be more interesting to go to the site with Japanese craftsmen and use Japanese materials to make it rather than building a store by Americans using American materials.

We collected waste materials in Kyoto, processed them to some extent, transported them to New York, and assembled them there with a Japanese construction company. In Kyoto, these waste materials are just garbage, but if you bring them to New York, they are prized and cherished and surprisingly good value for money. Japanese contractors work quickly and the labor cost is inexpensive. In addition, although the materials are scrap materials, they are materials that can only be obtained in Japan, so you can retain Japanese quality. I would like to continue taking old materials to New York, San Francisco, and other places where their value is recognized and appreciated.

And in Japan this year, we have an interesting project underway, requested by a client who wants to create a shop with a sustainable theme. Based on the idea of "not moving as much as possible," we decided to create a new store using scrap materials from buildings scheduled to be demolished in the surrounding area. When I applied for a house to be demolished on Instagram, I found it about 40 minutes from the planned construction site.

In Japan, due to regulatory issues, it can be difficult to use reclaimed materials in a new construction, however, in interior projects which have nothing to do with the structure - we integrate reclaimed materials.

2022年の夏にニューヨークのブルックリンで50 Norman(2022)というお店作り、そこでは京都の家屋解体時に出た廃材を活用しました。アメリカ人の手でアメリカの材料を使って、アメリカのお店を作るよりも、日本の職人と一緒に現地に向かい、日本の材料を持ち込んで作った方がきっと面白くなるなと思ったのがきっかけです。京都で廃材を集めてある程度加工しておき、ニューヨークに輸送して、日本の施工会社と一緒に現地で組み立てました。これらの廃材は京都だとただのゴミにしかなりませんが、ニューヨークに持っていけば大きな価値が生まれる。

そしてこの方法は意外とコストパフォーマンスが良いんです。日本人の施工業者は短時間で効率的に働くし、レイバーコストも安い。そして材料は廃材なので価格も安いですが、日本でしか得られない材料なので日本のクオリティが生み出せます。これからもニューヨークとやサンフランシスコのように、廃材の価値を認めてくれるようなところへ持って行ってプロジェクトがやりたいですね。

そして日本でも今年、サステナブルをテーマに店舗建築を作りたいというクライアントの要望があり、進行しているプロジェクトがあります。「できるだけ動かさないこと」を軸に、その周辺で解体される予定の建物から出た廃材を用いて新しい店舗を作ることにしました。インスタグラムで解体予定の家屋を応募したところ、建設予定地から40分ほどの場所に見つかったので、TANKという施工チームとともに、1日かけてリヤカーで材料を運び、店舗のデザインに使用します。

日本では規制の問題でまだ新築の建設ではほとんど使えないため、インテリアのように構造に関係のないところからスタートしていますが、いずれは建築全体で使えたらなって思っています。

You also redesigned a Sento [public bathhouse] in Sumida. I wanted to hear your views on Sento culture and a little bit about that project. I'm obsessed with Sentos and go all the time when I am in Japan.

東京の墨田区で銭湯の設計もされています。私は大の銭湯好きで、日本の滞在中は毎日通っていたくらいなので、長坂さんから見た日本における銭湯文化についてお聞きしたいです。

When I go on business trips to the countryside, I don't like showers in business hotels, so I often go to Sentos. Unfortunately, many Sento in Japan today are forced to close due to financial difficulties. The other day, I heard that a Sento that was important to me was about to close, and I tried to persuade them to stay open, but unfortunately, it closed. Seeing that, I always thought that I wanted to redesign an old place that would be accepted in the present age and leave it for the future.

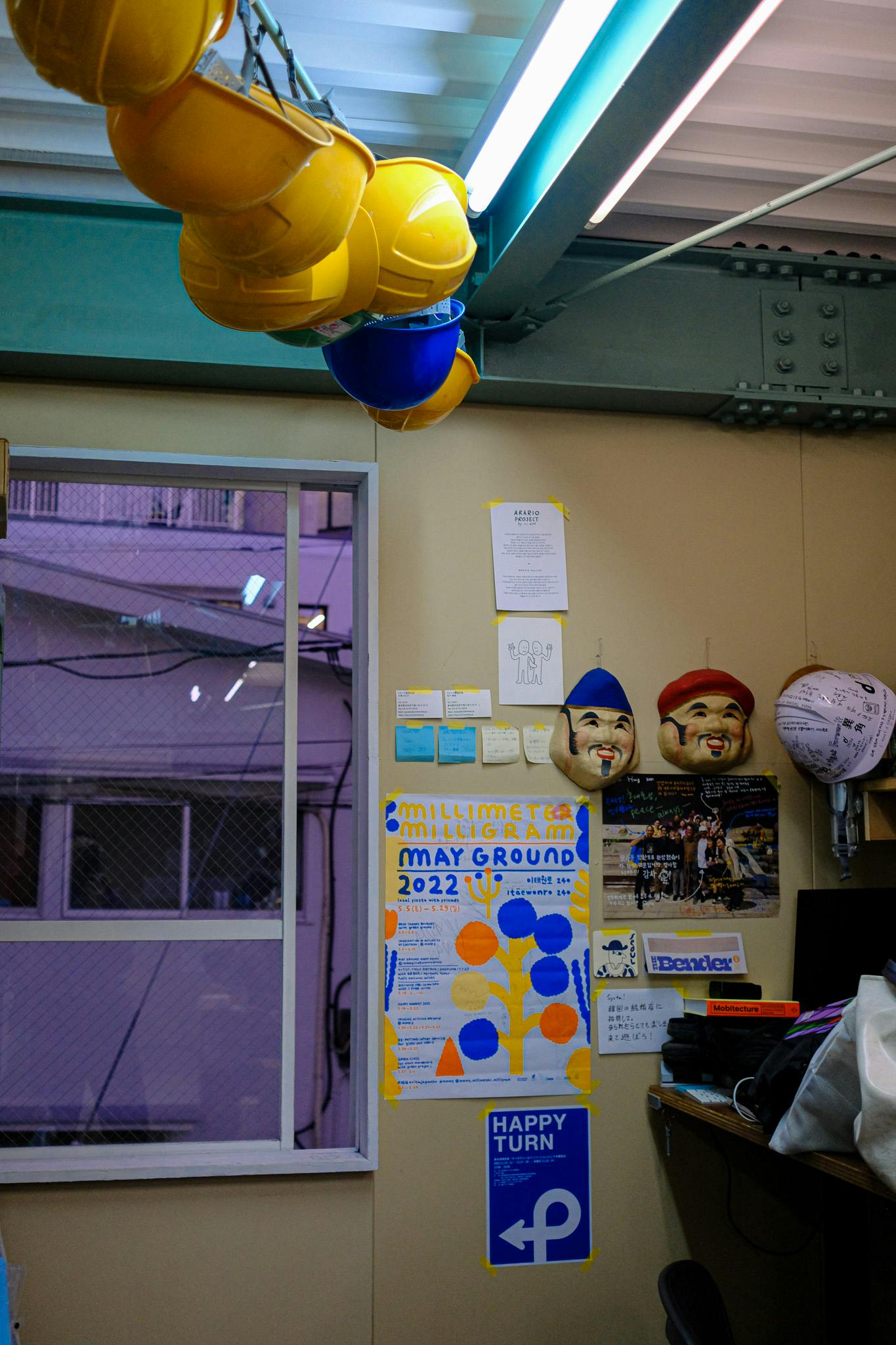

I place great importance on the aspect of "everyday life," and rather than creating a hall or a museum to feel "extraordinary," as I mentioned earlier, the process of creating everyday life is much more exciting. By chance, I was able to meet a wonderful client, the owner of Sento, and I was involved in a very valuable opportunity to think about the flow of Sento, which is quite a daily routine.

Sento is such a traditional business, and it's not traditionally an industry that asks for innovative designs. But since we're involved, we decided to create a new form of Sento rather than just making an existing one look a bit nicer. It's difficult to run a business just by providing the public bath service like before.

We had an idea to create a space that offers users a fulfilling ritual and relaxation space before bed. I proposed adding a little luxury to the night, such as turning on the sauna and creating a beer bar. That is how the current Koganeyu(2020) was born.

Recently, a renewed interest in Sento culture by younger generations has been a catalyst in it’s evolution. In their father's time, such new things were not allowed, but the next generation is gradually moving towards a new phase of Sento. That's why if we all work together to make Sento culture evolve to be a little more lively now, we'll be able to preserve as well as evolve this tradition for contemporary times.

地方に出張に行くとビジネスホテルに泊まるとシャワーが好きでなくて、僕もよく銭湯に行っています。でも残念なことに、いま日本では数々の銭湯が経営難になって、閉店を余儀なくされています。先日も僕にとって思い出深い銭湯が閉店してしまうことを聞いて、相当説得したんですが残念ながら閉館してしまいました。そんな状況を見て、銭湯が今の時代に受け入れられる場所へと、僕が手を加えることで将来に残していきたいということはずっと思っていました。

僕は「日常」っていう側面をすごく大事にしています。さっき言ったような「非日常」を感じるためのホールとか、ミュージアムみたいなものを作るより、日常を作る過程の方がとても重要です。その中で偶然、銭湯を営む素敵なクライアントに出会うことができ、銭湯というかなり日常的なフローに入りこむことできるような、とても貴重な機会に携わらせてもらうことができました。

銭湯って昔からある伝統的な業界で、本来は革新的なデザインを依頼するような業種じゃないんです。でも僕たちが携わるからには、風呂場を素敵に作るだけじゃない新しい形にしようと思いました。これまでみたいにお風呂に入って帰るだけじゃ、ビジネスとして成り立つことが難しい。だからサウナをつけたり、 ビールバーを作ったりして、夕方の寝るまでの時間をちょっと贅沢にするような、時間に膨らみを持たせることを提案しました。そこで生まれたのが現在の黄金湯(2020)の姿です。

最近は世代による変化もあって、銭湯がだいぶ見直されてる気がします。お父さんの時代は新しい試みが許されなかったけど、次世代によって、銭湯が新しいフェーズへ少しずつ動き出しているのかなと思います。だから今のうちにみんなで手をかけてもう少し盛り上げられれば、維持できるものが増えるのではないかと思っています。実は銭湯プロジェクトの第2弾として、また別のクライアントの改修にまさに取り組んでいます。