Studio Visit with 2M26

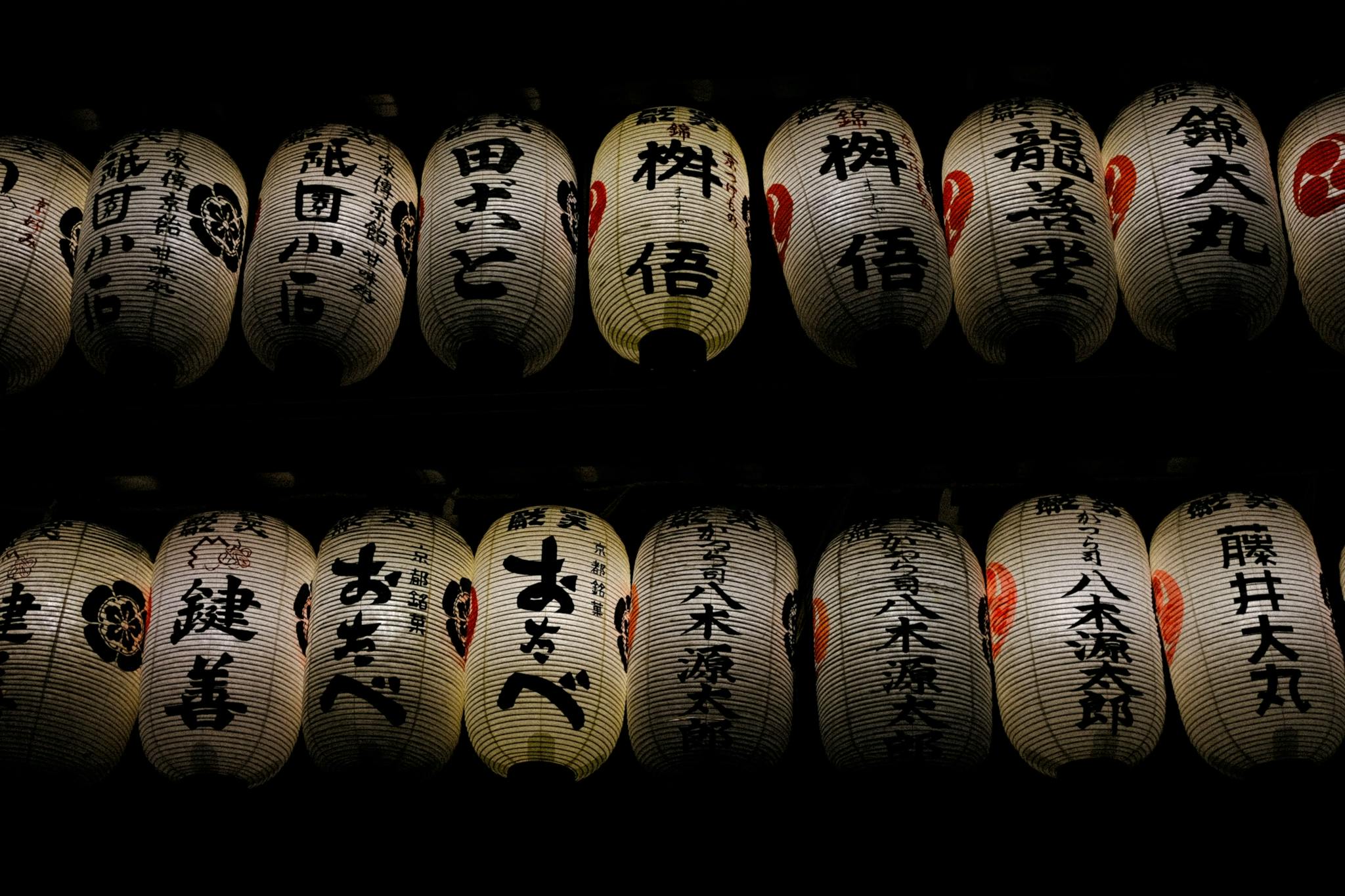

We do a studio visit in Kyoto, Japan, with architects 2m26

Despite only being 38km outside of downtown Kyoto, we felt utterly lost and far removed from civilisation in the Japanese countryside as we took winding roads alongside alpine-lined river banks.

For over a decade, French architects Sébastien Renauld and Mélanie Heresbach have engaged with Japan as both a site of inquiry and a field of practice, moving between craft, performance, and architecture. What began as an exploration of material traditions evolved into a series of site-specific interventions from Tokyo to Hiroshima, eventually grounding them in Kyoto—a city that serves as both a crossroads and a vantage point.

Their practice took shape in the wake of Japan’s financial and ecological crises, amid a generation of architects and makers rethinking how to live within the constraints of land and resources. Unlike in Europe, where such discourse often remains theoretical, here, adaptation is lived. Craft is not seen as a luxury but a quiet, ever-present logic—an ethos that informs not only their work but their lifestyle.

I sat down with Sébastien to discuss the differences between craft heritage and preservation in Europe and in Japan, restoring a traditional Japanese Kominka with respecting the indigenous technology of the architecture, living and working with and from the land and their multidisciplinary architecture practice.

Kristen_ What made you decide to move to Japan?

Kristen_ Qu’est-ce qui t’a poussé à déménager au Japon?

2m26_ We had been coming to Japan for about ten years. At first, we came to discover the local crafts by visiting a bath and a craftsman every day to really see Japan from north to south and all the things there was to learn. Later on, we did a performance art project in Tokyo and a renovation in Hiroshima and started getting commissions. Kyoto is a bit in the middle and it's easy to go from one place to another.

We got artist visas because our architectural practice was already under artist status in France.

Japan experienced a very big financial and ecological crisis between 2008 and 2011. As a result, there is a new energy coming from people between 30 and 50 and who are thinking about how to live together on a limited land. There was a dynamic that we didn't find in Europe, of how we manage to live together on earth. In addition to a crafts culture that is everywhere, you can even have unique handmade objects without luxurious price tags. That’s a pleasure to see.

2m26_ Cela faisait une dizaine d’années qu'on venait au Japon. Au début, on venait découvrir l'artisanat local en visitant un bain et un artisan tous les jours pour vraiment voir le Japon du nord au sud et toutes les choses à apprendre. On a ensuite réalisé un projet de performance artistique à Tokyo et une rénovation à Hiroshima.On a ensuite commencé à avoir des commandes. Kyoto, c'est un peu au milieu et c'est simple d'aller d'un endroit à l'autre.

On a commencé à avoir des visas d'artistes, car notre pratique d'architecture était déjà sous un statut d'artiste en France.

Le Japon a connu une crise financière et écologique très forte entre 2008 et 2011. Du coup, il y a une nouvelle énergie venant des personnes qui ont entre 30 et 50 ans et qui ont cette pensée de comment on vit ensemble sur un sol qui est limité. Il y avait une dynamique qu’on ne trouvait pas en Europe de comment on fait pour cohabiter sur terre. En plus d'une culture de la main qui est partout, tu peux même avoir des objets fait mains uniques et qui ne sont pas vendus au prix d'un objet luxueux. Ça, c'était un autre bonheur.

This culture of working with other communities, but also with animals, is another way of working and seeing life.

Cette culture de travail avec d’autres communautés, mais aussi avec les animaux, c’est une autre manière de travailler et de voir la vie.

We bought and renovated a big house in Kyoto which came with horses. Since the average age of the valley is 80 years old, we quickly understood that we would need help to maintain it and the land. Most of the techniques are linked to a simple and shareable farming know-how. The floor is clay, sand, and lime and you just beat it. Anyone can do it, but since it’s the entrance, construction companies will over-charge for this know-how. It's become luxurious. As a result, we quickly started to want to share because it's a magical thing to have an architecture that is constantly reparable in terms of woodworking know-how.

I had worked a lot in cities with large artistic projects that always involved other people. Once I moved to the countryside, I didn't want to be alone. So, we created the right conditions for people to come. You learn to work with what I call your environment, stones, trees, living beings, plants. The environment allows us to have materials because we take care of it. In summer, you thin your forest to recover small trunks that will make you the rafters, the bark of the tree to make roofs. In September, you cut the rice that makes ropes, shoes, and roofs. In October, bamboo. In November, the thatch is used to make the roof and in winter, you collect the construction wood.

On achète une grande maison à Kyoto qu’on rénove avec des chevaux qu’on nous offre. Comme la moyenne d'âge de la vallée est de 80 ans, on comprend assez vite qu'on va avoir besoin d'aide pour entretenir l'environnement. La plupart des techniques sont liées à un savoir-faire fermier simple et partageable. Un sol en terre battue c’est de l'argile, du sable, de la chaux et tu tapes. Tout le monde peut le faire, mais comme c'est la pièce d'entrée les entreprises de construction vont sur-facturer ce savoir-faire là. C'est quelque chose qui devient luxueux. Du coup, on commence assez vite à avoir envie de partager parce que c'est magique d'avoir une architecture qui se répare en permanence, en termes de savoir-faire pour le travail du bois.

J'avais beaucoup travaillé en ville avec des grands projets artistiques qui impliquaient toujours d'autres personnes. Quand je me retrouve à la campagne, je ne veux pas être tout seul. Donc on a créé les conditions pour que les gens viennent. On apprend à travailler avec ce que j'appelle le milieu, les pierres, les arbres, les êtres vivants, les plantes. L'environnement nous permet d'avoir des matériaux parce qu'on prend soin de lui. En été, tu vas éclaircir ta forêt pour récupérer des petits troncs qui vont te faire les chevrons, l'écorce de l'arbre pour faire des toits. En septembre, tu vas couper le riz qui permet de faire des cordes, des chaussures, des toits. En octobre, des bambous. En novembre, la chaume qui permet de faire le toit et en hiver, tu vas récupérer le bois de construction.

How did you learn to work with your environment?

Comment as-tu appris à travailler ainsi avec ton environnement?

By living here, it's around you, the material may have travelled 30 metres from where it grew to the roof. The know-how for bark roofs has somewhat disappeared because it's not noble enough and you can’t find any more craftsmen. We started by making a small chicken coop with a bark roof to try our hand.

À force d’habiter ici, c'est autour de toi, le matériau il a peut être fait 30 mètres entre là où il a poussé et le toit. Pour les toits en écorce, le savoir-faire a un peu disparu parce que ce n'est pas assez noble, il n’y a plus d'artisans. D'où le fait d'avoir fait d'abord un petit poulailler avec un toit en écorce pour commencer.

Your philosophy of architecture seems to revolve around the seasons, can you tell me a little more about it?

Ta philosophie de l’architecture semble tourner autour des saisons, peux-tu m’en dire un petit peu plus?

Summer is very hot and humid in Japan. As a result, most materials rot if they’re not ventilated. We made our first earth walls that catch and release moisture day and night, but also according to the seasons. Their entire architecture is based on this idea, how to manage 38°C with 99% humidity, whether in the way of selecting the wood or how to make the roofs. These are only natural ventilation systems. The question is how can we make sure they last as long as possible? But we have to respect the climate and build ecologically because the house and the environment want that.

Au Japon, l'été est quand même une saison très particulière où il fait très chaud et humide. Du coup de la plupart des matériaux s’ils ne ventilent pas ils pourrissent. On a fait nos premiers murs en terre qui attrapent et relâchent l'humidité jour et nuit, mais aussi suivant les saisons. La totalité de leur architecture est basée sur cette idée là, comment gérer 38°c avec 99 % d'humidité que ce soit dans la manière de sélectionner les bois ou comment faire les toits. Ce ne sont que des systèmes de ventilation naturelle. Comment peut-on faire en sorte que ça tienne le plus longtemps possible? Mais il faut respecter le climat, faire une construction écologique parce que la maison et l'environnement veulent ça.

You’re originally from Nancy. Are there any technologies for architecture there?

Tu es originaire de Nancy. Existe-t-il des technologies pour l’architecture là-bas?

Not much, no. We don't really know how to do stone walls anymore. Traditional know-how is minimal compared to Japan, which is lucky enough to have kept all its rural know-how because Japan focuses on preserving the know-how rather than the object. Whereas in Europe, we preserve the object. The living treasure in Japan is the humans, it's not what they do. They managed to preserve their know-how for much longer, in particular through the Industrial Revolution of 1890 and 1920, at a time when these were disappearing in Europe.

Plus trop. Les murs en pierre, on ne sait plus vraiment les faire. Les savoir-faire traditionnels sont vraiment minimes comparé au Japon qui a la chance d'avoir gardé tous ses savoir-faire ruraux parce que le Japon préserve le savoir-faire et non pas l'objet. Alors qu'en Europe, on préserve l'objet. Le trésor vivant au Japon, c'est un humain, c'est pas ce qu’il fait. Ils ont réussi à conserver des savoir-faire beaucoup plus longtemps, et notamment à travers la révolution industrielle de 1890 et 1920 où en Europe, ils ont juste été effacés.

If it is difficult to find craftsmanship in the younger generations, how is this know-how passed on?

S’il est difficile de trouver de l’artisanat dans les jeunes générations, comment ce savoir-faire se perpétue-t-il ?

It's difficult. It takes the younger generation longer to learn and improve since they get fewer orders. It also requires them to do something very hard for a Japanese person, which is to rebuild the learning system they had. For us, if we’re interested in something we try our hand at it whereas a Japanese craftsman will have learned by imitation of a master. Some craftsmen are starting to get creative again about the materials they use and how they can make them evolve. But this is relatively recent.

C’est difficile. Avec moins de commandes, la jeune génération met plus longtemps à apprendre et se perfectionner. Ça leur demande aussi de faire quelque chose qui est très dur pour un Japonais qui est de reconstruire le système d'apprentissage qu'il a eu. Nous, si on voit quelque chose qui nous intéresse, on essaye de le faire. Un Japonais. Il aura appris par imitation d'un maître. Il y a quelques artisans qui recommencent à faire preuve de créativité sur les matériaux qu’ils utilisent et comment ils peuvent les faire évoluer. Mais c'est relativement récent.

I've also noticed that it's much more collaborative here and more generous.

J'ai aussi remarqué que c'est beaucoup plus collaboratif ici et plus généreux.

Everyone recommends projects to each other in Japan. There is no real competition, even between architects.

A craftsman in Kyoto will know how to do something very well and he will be the best at it, on the other hand, it's only one thing. Whereas in the countryside, you’ll find people with multiple skills. Someone will have a basic job, but they also know how to grow rice, work with wood and make a thatched roof. There is a Japanese word for the man of a hundred skills, which refers to the farmers.

Au Japon, tout le monde se refile des projets. Il n'y a pas vraiment de compétition interne, même entre architectes.

Un artisan à Kyoto saura faire super bien un truc et ça sera le meilleur, par contre, c'est un seul truc. Alors qu'à contrario, à la campagne, il y a encore des savoir-faire multiples. Quelqu’un aura un métier de base, mais il sait aussi cultiver le riz, travailler un peu de bois et faire un toit en chaume. Il y a un mot japonais pour dire l'homme aux cent savoir-faire ce qui désigne le fermier en fait.

Are there many local artisans you collaborate with and how do you find them?

Y a-t-il beaucoup d’artisans locaux avec lesquels tu collabores et comment les trouves-tu ?

Yes, we found a blacksmith who is ultra-specialised in hooks or hinges via social media. We've never met him, but it's a pleasure to collaborate with him. The result is always better than our designs.

And we found a community on social media to redo the roof.

Oui, par exemple, on a trouvé un forgeron ultra spécialisé pour les crochets ou les gonds via les réseaux sociaux. On ne l'a jamais rencontré, mais c'est un bonheur de collaborer avec lui, il fait toujours mieux que notre dessin.

Pour refaire le toit, c'est une communauté rencontrée sur les réseaux sociaux qui est venue.

How did you go about rebuilding the roof?

Comme ça s’est passé par exemple quand tu as construit le toit ?

Firstly, we met a professional who agreed to let us work alongside him because he likes the idea of sharing the know-how and he wants it to remain alive. That’s not a given. Then we had other Japanese and European friends come and help us. Given the fact that roofs are rarely redone entirely, except when rebuilding temples, it’s great to get the opportunity to see the whole process for once.

The plant used for the roof is now a plant used in the United States and Europe to make biofuels, except that they use the American version which is 4.5 metres high. They only use the base and so we use their waste for the roof. We have French friends who have an unlimited supply because the farmer next to them decided to make biofuel. So, they end up redoing thatched roofs thanks to this sector’s waste and it turns out it’s the perfect material to make roofs.

D'abord, on a rencontré un professionnel qui était d'accord pour qu’on puisse l'aider car il adhère à cette logique du savoir-faire qui se partage et il veut que ça reste vivant. Ce qui n’était déjà pas gagné. D'autres amis japonais, européens sont venus. Sachant que plus personne ne va refaire un toit en entier, à part un temple, l'avantage était d'avoir pour une fois le processus complet.

La plante qu'on utilise pour le toit est maintenant une plante utilisée aux États-Unis et en Europe pour faire des biocarburants, sauf qu'ils utilisent la version américaine qui fait 4,5 mètres de haut. Ils n’utilisent que la base et du coup on utilise leurs déchets pour le toit. On a des amis français qui ont ce matériau en quantité illimitée, parce que le paysan à côté de chez eux a décidé de faire du biocarburant. Donc ils vont finir par refaire des toits en chaume grâce aux déchets de cette filière qui sont le matériau parfait pour faire des toits.

How were you greeted by the local communities?

Quel accueil as-tu eu de la part des communautés locales ?

We were lucky because it's a rather welcoming valley. They understood that given the average age, they were going to need help. When you start harvesting for the thatched roof, you earn kudos to be part of the community. They weren’t sure if we were just here to renovate the house and leave. But we have two horses, dogs, and cats, so we're more likely to stay.

On a eu de la chance parce que c'est une vallée plutôt accueillante. Aussi ils ont bien compris qu’étant donné la moyenne d’âge, ils allaient avoir besoin d'aide. Quand on commence à récolter pour le toit en chaume, on gagne des points pour faire partie de la communauté. Ils se sont demandé si on allait juste rénover la maison et partir. Mais on a quand même deux chevaux, des chiens, des chats, donc on est plus parti pour rester.

What do your clients' projects look like?

À quoi rassemblent les projets de vos clients ?

We have many different orders. Home renovations, small new buildings, scenographies for museums, small mobile restaurant projects.

On a pas mal de commandes différentes. Des rénovations de maisons, des petits bâtiments neufs, des scénographies pour des musées, des petits projets de restaurants ambulants.

You get them through word of mouth or via social media.

C’est du bouche à oreille ou via les réseaux sociaux.

Word of mouth first, even if social media is very strong in Japan as well as throughout the world.

Bouche à oreille d'abord, même si les réseaux sociaux sont très forts au Japon comme dans le monde entier.

Reconciling that with the life of a farmer must be a lot of work?

Concilier cela et la vie de fermier doit représenter beaucoup de travail ?

Well, we’re two here and the animals help too. So, it’s never been a problem in itself. We are first and foremost architects, and we live in an environment that provides us with materials. I don't cultivate a forest, I just try to maintain it as it should be because the previous owners had stopped doing it. We can talk about it again in ten years when the environment is ready to be cultivated again. We’ve only planted fruit trees for now. We haven’t replanted construction wood because there is plenty of it and no one takes care of it.

On est deux et les animaux aident aussi. Donc ça n'a jamais été un problème en soi. Après on est d'abord des architectes et on vit dans un environnement qui nous fournit des matériaux. Je ne cultive pas une forêt, j'essaye juste de l'entretenir comme elle devrait l’être, parce que les anciens propriétaires avaient arrêté de le faire. On peut en reparler dans dix ans quand l'environnement sera prêt à de nouveau être cultivé. Jusqu'alors, on n'a planté que des arbres fruitiers. On n'a pas replanté du bois de construction parce qu'il y en a plein et que personne ne s'en occupe.

How did you learn to build the Japanese way?

Comment as-tu appris à construire à la manière japonaise ?

It's not very complicated. Two reference books give basic ideas about the styles. But it's more about learning by doing and applying common sense. When I start renovating the house, I sit on my computer and think about what order I'm going to put the pieces in, and how they're actually put together. We have mortise and tenon equipment in Europe too. It's a little different here because it's not the same woods, not the same tools and we can do things more easily, but the way to go about it is the same. You also learn a lot by taking buildings apart.

Ce n'est pas très compliqué. Il y a deux livres qui donnent des idées de base sur les genres. Mais c’est plus en faisant qu’on apprend, c'est surtout une histoire de logique. Quand je commence à rénover la maison, je suis obligé de m'asseoir sur mon ordinateur et de penser dans quel ordre je vais mettre les pièces, comment elles sont véritablement rassemblées. Une tenon-mortaise, on en a en Europe. Ça diffère un peu ici parce que ce n'est pas les mêmes bois, pas les mêmes outils et qu'on peut plus facilement faire des choses, mais la logique reste la même. On apprend aussi beaucoup en démontant des bâtiments.

Do you call on outside help?

Tu fais appel à de l'aide extérieure?

Depending on the size of the projects, we ask friends or acquaintances and certain craftsmen. In most cases, if you're just an architect, it's very complicated to make a profit because you're only paid for your brain time. So, we would have to build two houses a year. Whereas we can make a living out of building what we design.

From time to time, we work in a group, but it's not that easy to build a team of craftsmen. They say it takes about twenty-five years.

I don't want to use glue, I want to be able to assemble and disassemble myself. For example, for the doors, I use a Japanese system with two studs, but I don't do it with the traditional Japanese detail as it would take me too much time. So we simplified a lot of things by looking at how a door is made and by saying what I could do with my current knowledge, and what I can learn through the manufacturing process. We are much closer to the Japanese architecture of a few centuries ago than to the way they did things just before the Second World War or even before the big industrialisation. There are a lot of things that seem Japanese because they reuse Japanese signs or ways of doing, but they are really another interpretation of what we think is beautiful.

Each region has its style of thatched roof, we created the style of where we are. We did it our way. It works because we're not Japanese.

And I don't speak Japanese or very little. And I think it was also an advantage for learning. I have to work with them and we understand each other by doing so, and I learn things in the process. I don't have the know-how delivered to me. Every time they show me something, I think about why they're doing it this way.

Suivant la taille des projets, on demande à des amis ou des connaissances, à certains artisans. Mais dans la plupart des cas, si on est qu'architecte, c'est très compliqué de dégager des bénéfices parce que tu n’es rémunéré qu’à ton temps de penser. Donc il faudrait qu'on fasse deux maisons par an. Alors que si on construit ce qu'on dessine du coup, cela nous permet de vivre de ça.

De temps en temps, on s'associe mais ce n'est pas si simple de construire une équipe d'artisans. On dit que ça prend quand même vingt-cinq ans.

Je ne veux pas utiliser de colle, je veux pouvoir monter, démonter par exemple, les portes, j'utilise un système japonais qui est à deux tenons mais je ne fais pas le détail traditionnel japonais qui me prendrait trop de temps. Donc en regardant comment est fait une porte et en se disant comment je peux faire avec mes connaissances actuelles, qu'est ce que je peux apprendre à travers le processus de fabrication, on a quand même simplifié beaucoup de choses. Donc on est beaucoup plus proche d'une architecture japonaise d’il y a quelques siècles que des manières de faire juste avant la seconde guerre mondiale voir avant la grosse industrialisation. Il y a beaucoup de choses qui paraissent japonaises parce que ça réutilise les signes ou le sens japonais, mais qui en vrai sont autre interprétation de ce qu'on pense être beau.

Chaque région a un style de toit en en chaume, là on a créé le style d’ici. On a fait notre propre manière. Donc ça marche, parce que nous ne sommes pas Japonais.

Et je ne parle pas japonais ou peu. Et je crois que ça a été aussi un avantage pour apprendre. Je suis obligé de faire avec eux. Et du coup, en faisant, on se comprend et j'apprends des choses. Je n'ai pas un savoir qui est livré. À chaque fois qu'ils me montrent un truc, je me pose la question de pourquoi ils sont en train de faire ça.

You told me about your use of metal with regard to humidity.

Tu m’as parlé de ton utilisation de métal par rapport à l’humidité.

Take the renovation, I'm doing with the tatami mats. I’m putting the floor and logically I would have fixed the boards that are under the tatamis. In the next room, the boards are not fixed, which means I can remove them. My first thought is that this way it's more practical to repair things under the house. If I insert pieces of metal into the floor, it will attract moisture, my board will mould, and my tatami will be damaged.

I'm coming up with the process because no one told me whatever you do, don't fix them to the floor. Sometimes it's because they're lazy. But in this case, there's a reason behind it, knowing that the tatami is a big sponge for humidity.

Par exemple, dans la rénovation que je suis en train de faire avec des tatamis. Je me retrouve à mettre le plancher et logiquement j'aurais dû fixer les planches qui sont sous les tatamis. Sur la pièce d'à côté les planches sont libres, je peux les enlever. Ma première pensée, est que c’est quand même plus pratique pour réparer des choses sous la maison. Si j'insère des bouts de métaux dans le plancher, du coup ça va attirer l'humidité, ma planche va moisir et mon tatami va être endommagé.

Je recrée le processus parce que personne ne m'a dit ‘surtout il ne faut pas les fixer’. Parfois c’est parce qu’ils sont feignants. Là, il y a une raison derrière, sachant que le tatami est une grosse éponge à humidité.

What are your upcoming projects?

Quels sont vos projets à venir ?

We have just started to renovate the house, as it took us two years to harvest the thatch to redo the roof.

One of our dreams is how our actions can change the laws that are in place. Typically, in Kyoto, it’s forbidden to build new thatched buildings even though they advocate sustainable development. We bought the land behind it with that little house that’s not pretty, and we are going to rebuild a new building with a thatched roof. We're going to call the city and advocate for the law to change. It grows everywhere, and it's good for the environment, so why is the law still so dumb?

On vient de commencer à rénover la maison, comme ça nous a pris deux ans pour récolter la chaume pour pouvoir refaire le toit.

Un de nos rêves, c'est comment nos actions peuvent changer les lois qui sont en place. Et typiquement à Kyoto, c'est interdit de construire des bâtiments neufs en chaume bien qu’ils prônent le développement durable. On a acheté le terrain qui est derrière avec la petite maison qui n'est pas belle et on va reconstruire un nouveau bâtiment avec un toit en chaume. On va appeler la ville en disant qu’il y a un problème pour que la loi change. Ça pousse partout, ça fait du bien à l'environnement donc pourquoi la loi est toujours aussi bête.

Do you think it will pass, or they are too rigid?

Est-ce que tu penses que ça va passer ou qu'ils sont trop rigides ?

You have to consider the conservative side of Japan together with the fact that to be so conservative you have to be flexible. If Japan wants to keep its national identity, it’s customary to accept changes and digest these changes.

Here, the harmony of the community takes precedence. The law can be a grey area because the goal is to achieve a win-win situation. That's why it's a culture that is quite pleasant to live in.

Il faut bien prendre en compte le côté conservateur du Japon sur le fait que pour être aussi conservateur il faut que tu sois flexible. Si le Japon veut garder son identité nationale, il a d'usage d'accepter des changements et de digérer ces changements.

Ici c'est l'harmonie de la communauté qui prime. La loi, elle est grise parce que le but du jeu, c'est qu'à la fin chacun y gagne. C'est pour ça que c'est quand même une culture qui est assez agréable à vivre.

Can you tell me a little about the philosophy of respecting what the house wants, and not just taking Western comfort criteria?

Peux-tu me raconter un peu la philosophie de respecter ce que veut la maison, et pas seulement prendre des critères de confort occidentaux ?

All Japanese architecture is repairable. Like the Argos boat from Greek mythology where they change all the parts and, in the end, it's still the same boat, even though there's not a single original piece of wood anymore. It's the same with their house. Since the climate is not kind to the materials, you keep changing parts. The way of building simplifies this and makes sure to let the materials breathe, otherwise your house will rot super quickly. Hence the fact that Japan is also built a lot on concrete and steel, sidestepping this idea of repairability.

When we build small autonomous structures, we really make an architectural gesture in the sense that there is a thought about the building. When we renovate a house, our first intention is to engage with this building to find out what we want. It's often about erasing the renovation of the '60s to '80s, which mainly consisted of adding a layer and plywood. We want to regain the flexibility of these houses. This means that there is no given use. You can use it as an office, a dining room or a bedroom. We really try to continue working with the house as much as we can.

On the other hand, being European, we enjoy having a view. So, we’re opening the area where the stable was to let more light in. But we also won’t re-insulate the house with a bubble that hinders the ventilation. If you base your ventilation on a technology, the day there is no electricity, the house rots. We try to pay attention to this, knowing that the Japanese idea of insulation prevention for winter is the engawa technique with two doors leading to your central room. There are houses where you really have a winter bedroom surrounded by rooms that are themselves surrounded by an engawa.

Toute l'architecture japonaise est une architecture qui se répare. Comme le bateau Argos de la mythologie grecque où ils changent toutes les pièces et à la fin, c'est toujours le même bateau, mais il y a plus un seul bout de bois d'origine. C'est exactement la même chose avec leur maison. Comme le climat n'est vraiment pas favorable aux matériaux, tu n'arrêtes pas de changer des pièces. Donc la manière de construire simplifie cela et veille à laisser respirer les matériaux, sans quoi ta maison va pourrir super vite. D’où le fait que le Japon est beaucoup construit en béton et en acier aussi, où c'est plus du tout cette logique de réparabilité.

Quand on construit des petites structures autonomes, on fait vraiment un geste architectural dans le sens où il y a une pensée sur le bâtiment, autant quand on rénove une maison, notre première intention, c'est de discuter avec ce bâtiment pour savoir ce dont on a envie, souvent c’est d'effacer la rénovation des années 60 à 80, qui consistait principalement à remettre une couche et des contreplaqués. On veut retrouver la flexibilité de ces maisons. Cela veut dire qu’il n'y a pas d'usage particulier. Tu peux l'utiliser en bureau, salle à manger ou chambre. On essaye de vraiment continuer à travailler avec la maison autant qu'on peut.

Le contre-exemple, c'est qu’étant européen, on a plaisir à avoir une vue. Donc le coin où il y avait l'écurie, on va en profiter pour ouvrir et avoir plus de lumière. Mais de l'autre côté, on ne cherchera pas à réisoler la maison avec une bulle qui empêche la respiration. Si tu bases ta respiration sur une technologie, le jour où il y a plus d'électricité, la maison pourrie. On essaye de faire attention à ça, sachant que la logique japonaise de prévention d'isolation pour l'hiver c'est la technique de l'engawa, d'avoir deux portes et ta pièce en partie centrale, sachant qu'il y a des maisons où tu as vraiment la chambre à coucher d'hiver entourée de pièces qui, elles-mêmes sont entourées d'engawa.

In such a system you told me all the materials have to last a very long time.

Dans un tel système tu m’as dit tous les tous les matériaux doivent durer très longtemps.

The best way to preserve wood is to put it in water. What it doesn't like is to have a very wet end and a very dry end. So, it's better to have an indoor environment that is relatively homogeneous. Thatched roofs are 100% humidity every morning, all year round.

Many foreigners want, and it has become a fashion, the decorum of Japanese rural life. The Japanese on the other hand no longer want to live in houses, or if they do it’s in a house that heats up quickly and without maintenance. In any case, the house loses its value after seven years. What I'm doing doesn’t make sense from a Japanese point of view. I put human energy or money into something that I will not be able to resell at cost.

The price of real estate in Japan has still not reached the world market price. As a result, a lot of Americans think that they can live in very nice houses. They bubble up inside where you can't see the initial structure, but the structure inside the house doesn't breathe anymore, so it will rot much faster.

For us, beauty is a purpose, it’s something that works with the local climate and can be repaired easily, that’s the beauty of it.

Most human beings today start by looking at how beautiful it is. It attracts a new dynamic in Japan too, but at the same time, I’m not sure it’ll help to preserve know-how.

Le meilleur moyen de conserver le bois c’est de le mettre dans l’eau. Ce qu'il n'aime pas, c'est avoir un bout très humide et un bout très sec. Donc il vaut mieux avoir un environnement intérieur qui est relativement homogène. Le toit en chaume, c'est 100 % d'humidité tous les matins, toute l'année.

Beaucoup d'étrangers veulent et c'est devenu une mode, le décorum de la vie rurale japonaise, sachant que les Japonais ne veulent plus habiter dans des maisons, ou alors une maison qui se chauffe vite et sans entretien. De toute manière, la maison au bout de sept ans n'a plus de valeur. Ce que je suis en train de faire, c'est une hérésie d’un point de vue japonais. J’injecte de l'énergie humaine ou de l'argent dans quelque chose que je ne pourrai pas revendre au prix coûtant.

Le prix de l'immobilier au Japon n'a toujours pas atteint le prix du marché mondial. Du coup, pas mal d’américains se disent qu’ils peuvent vivre dans de très belles maisons. Ils refont des bulles à l'intérieur où tu ne vois plus l'état de ta structure, mais la structure à l'intérieur de la maison ne respirant plus, elle va pourrir beaucoup plus vite.

Pour nous, le beau est une finalité, ça colle très bien au climat, c'est quelque chose qui peut être réparé facilement et c'est beau.

La plupart des êtres humains à l'heure actuelle commencent par dire que c'est beau. Ça attire une nouvelle dynamique au Japon aussi mais en même temps, ce n'est pas sûr que ça aide à préserver les savoir-faire.

I appreciate that view. I would not have thought about how all these additions can be a burden on the building.

J’apprécie ce point de vue et ce n’est pas quelque chose auquel j’aurais pensé, tous ces ajouts qui peuvent nuire au bâtiment.

There are plenty of ways that could work, for example, in the house we bought in Kyoto, the traditional structure was already destroyed. The previous owner had destroyed all the tatami rooms. And it's much easier to consider this ‘umbrella’ inside which we rebuilt an insulated wooden structure.

It's not contradictory, you can live in a house like this and still expect the level of comfort you want to have. But you have to do it without accelerating the deterioration process of the house. And above all, you need to be able to repair the house.

Il y a plein de logiques qui pourraient marcher, par exemple, la maison qu'on achète à Kyoto, la structure traditionnelle était déjà détruite. Le propriétaire d'avant avait détruit toutes les pièces à tatamis. Et donc là, c'est beaucoup plus simple de considérer qu’on a un parapluie et qu’à l'intérieur, on a reconstruit une structure en bois qui elle était isolée.

Ce n'est pas antinomique, c'est ce n'est pas parce que tu habites dans une maison comme ça qu'elle ne peut pas accepter le niveau de confort que tu souhaites avoir. Il faut que tu le fasses sans accélérer la détérioration d'une maison. Et il faut surtout que tu puisses toujours réparer cette maison.