Home Visit with Kyoichi Tsuzuki

We visit the cult-editor Kyoichi Tsuzuki at his Tokyo apartment and self-initiated 'Museum of Roadside Art.'

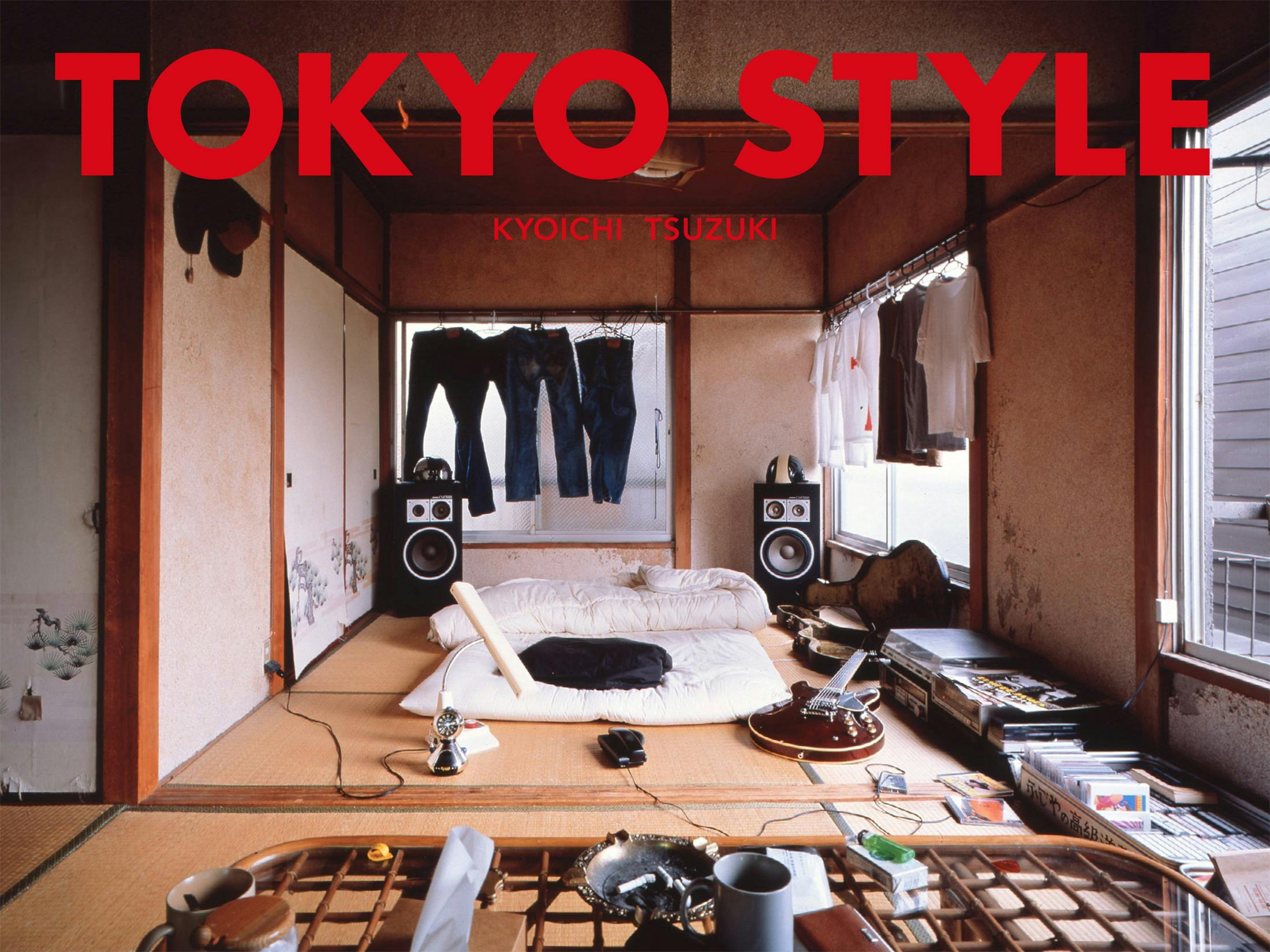

I am generally excited about all of the interviews and studio visits we do; after all, I am the one who chooses whom we reach out to invite for a discussion. But there has never been an interview I was THIS excited about. Kyoichi Tsuzuki is one of my professional idols. As a teen, there was one book or, probably at the time, a photo series I saw on Tumblr (or whatever was before Tumblr) which informed my entire idea of Japanese youth, their interiors and lifestyle – Kyoichi Tsuzuki's TOKYO STYLE.

Editor, Photojournalist and Storytelling Renaissance Man Kyoichi Tsuzuki disregarded all rigid protocols on how to build one's career in Japan and followed his curiosity in any direction it led him. If he couldn't get his work into a commercial magazine, he made his own magazine. If he didn't have the budget to hire a professional photographer, he bought a camera and took his own photos to accompany his essays. If Culture Ministries wouldn't purchase and preserve collections from rural Japanese Sex Museums on the brink of bankruptcy, he bought them and made his own Museum.

We sat down at home with Kyoichi to discuss his extemporaneous career, Mom Art, the adventurous world pre-internet and later visited his self-initiated Museum, The Museum of Roadside Art.

Kristen_ Journalist, Artist, Photographer, Editor, Cultural Sociologist, How would you define yourself and what you do?

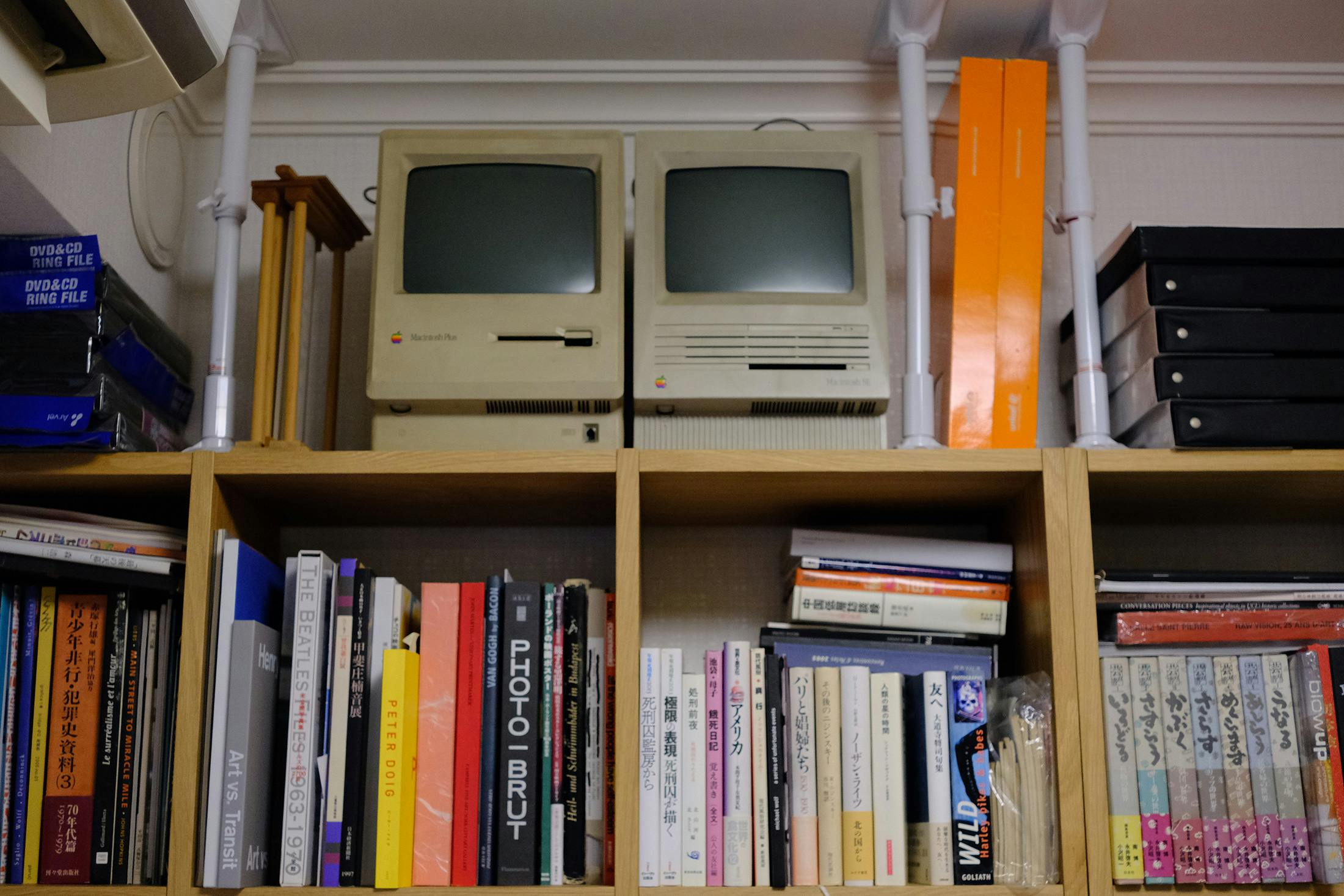

Kyoichi_ No, I'm just an editor. I started working in a magazine office and began making books. But still, my main job is as an editor or maybe a journalist as I also take photographs, purely for the economic reason that most of the projects that I do, don’t have enough budget to hire a professional photographer. So that's why I had to do it by myself.

With that being said, I have also had photo exhibitions in museums. But in a way, I'm not really trying to take photographs in an artistic way because you have to choose which direction you go – to be an art photographer or photojournalist. So I think it's really different to how to see the objects that you take photos of and how to express that. So, I'm trying to stay more in the journalism field.

My main goal is not to “serve the rich Prince” but rather to make books or web magazines to show what I saw.

Is it important to define ourselves or what we do?

K_ Yes, of course. I didn't realise that at first when I started to photograph, but then I started to think about it a lot. Like for example, the art photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, who is my close friend and also one of the biggest photographers in Japan, perhaps also around the world. He also photographed inside Wax Museums and showed them in his own exhibitions, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I also photographed the same place and published it in my book.

After seeing the exhibition, the people who go to see Hiroshi tell him, "What beautiful photographs!" but they never ask him, "Where did you take this?".

When I do an exhibition and shows of similar photos, I'm more pleased to hear responses like “Where can we go to see this?”. So that's the difference, I think. It's not that one is better than the other, but just a difference in attitude towards the work.

Do you approach your work in a way that is about telling stories that you find interesting and hope that it piques the curiosity of others who have not seen it before?

K_ My main output is a weekly mail magazine, which I send every Wednesday morning, and the price of it is 1000 yen for four articles in a month. Most of the readers are busy with working or housework and whatever or cannot afford to go because of the money. So I go for them. I visit places like Paris to see strange museums or countries far away from Japan and take photos and write the text and give those stories to the readers, and so then they pay me for it.

There are so many unknown artists who are energetic and have been doing strange things over the years, like an eighty-year-old guy making strange objects in his garden, which the neighbourhood hates. I want to get his or her energy and give it to the readers. These types of stories might be a small encouragement for our readers. So those are the two reasons.

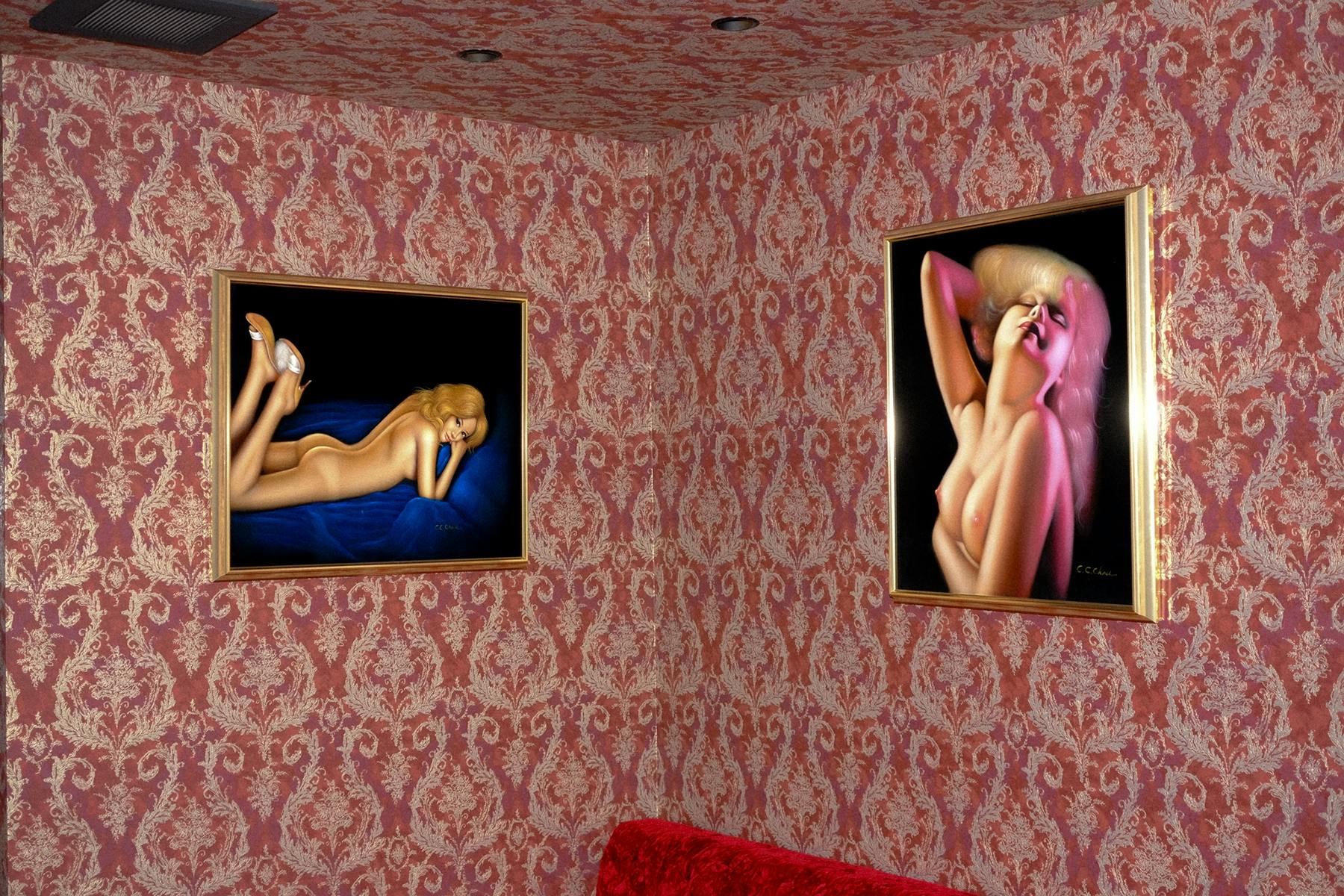

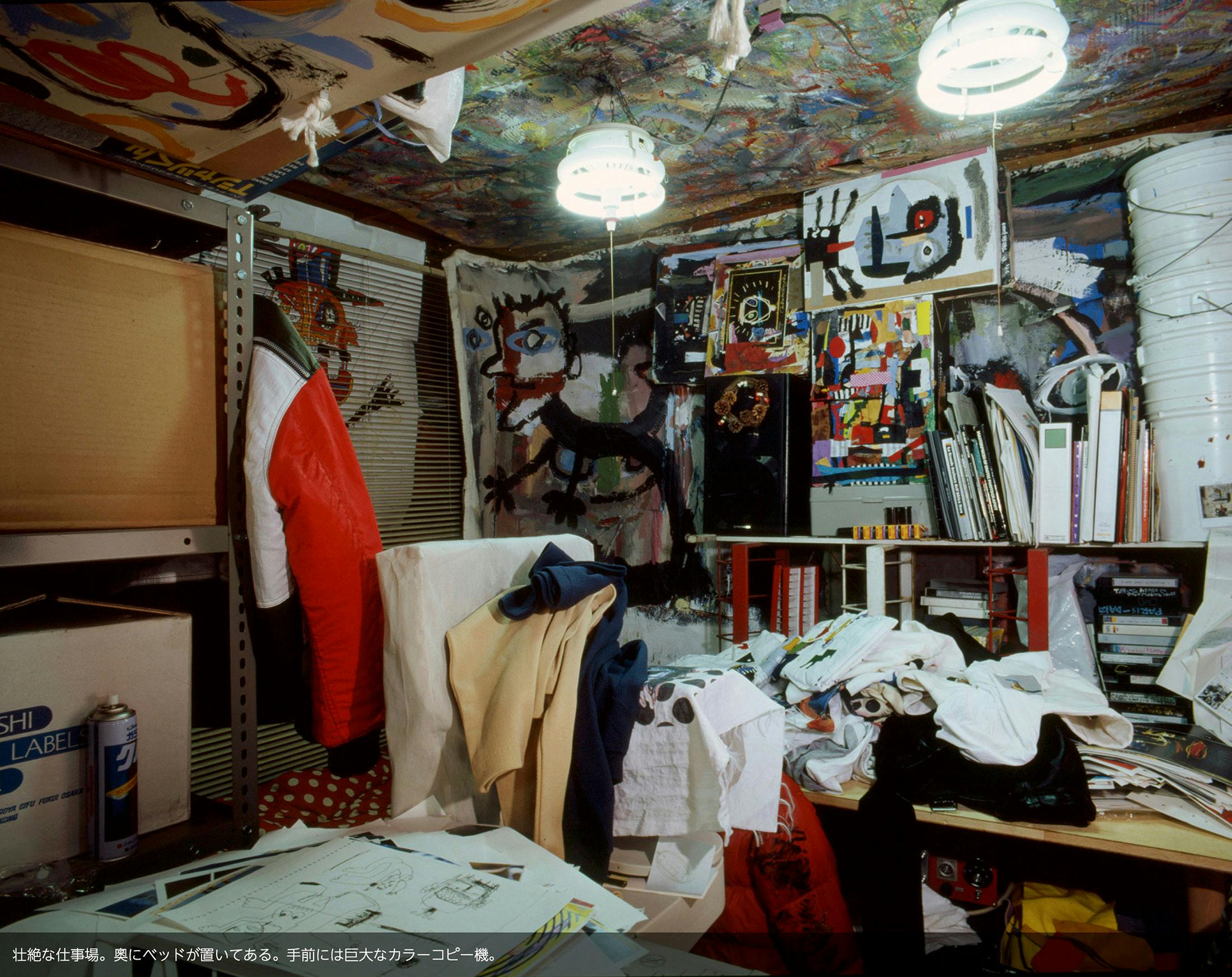

We opened a small museum, cafe/bar place, "大道芸術館"(Daidougeijutsukan) in Tokyo, to show my collection of bizarre art. I'm not a collector in any way, but the way I see it, I meet a lot of strange artists, and sometimes I want to buy to encourage them, and sometimes I have to buy to get the interview. So, over the years, I have acquired many strange collections ready to be shown. The collection was in storage all of this time, but we got a new place, and I put my collections there. If you see those “bad” unrefined or strange art in a simple story, that's just bad art – but if you show it the proper way, frame it nicely and do everything [to exhibit the pieces properly], it gives it a new context. So it depends on how you should represent it. That has also been an interesting experiment. But anyway, it’s a fun place.

Therearesomanyunknownartistswhoareenergeticandhavebeendoingstrangethingsovertheyears,likeaneighty-year-oldguymakingstrangeobjectsinhisgarden,whichtheneighbourhoodhates.Iwanttogethisorherenergyandgiveittothereaders.

Kyoichi Tsuzuki

I read that you began documenting ordinary Japanese people's homes, interiors, spaces, and phenomena because it was a more accurate portrayal of contemporary Japanese life. "There are more people who have visited love hotels than who own homes by Tadao Ando."

How do you think Japan is portrayed in the media vs reality?

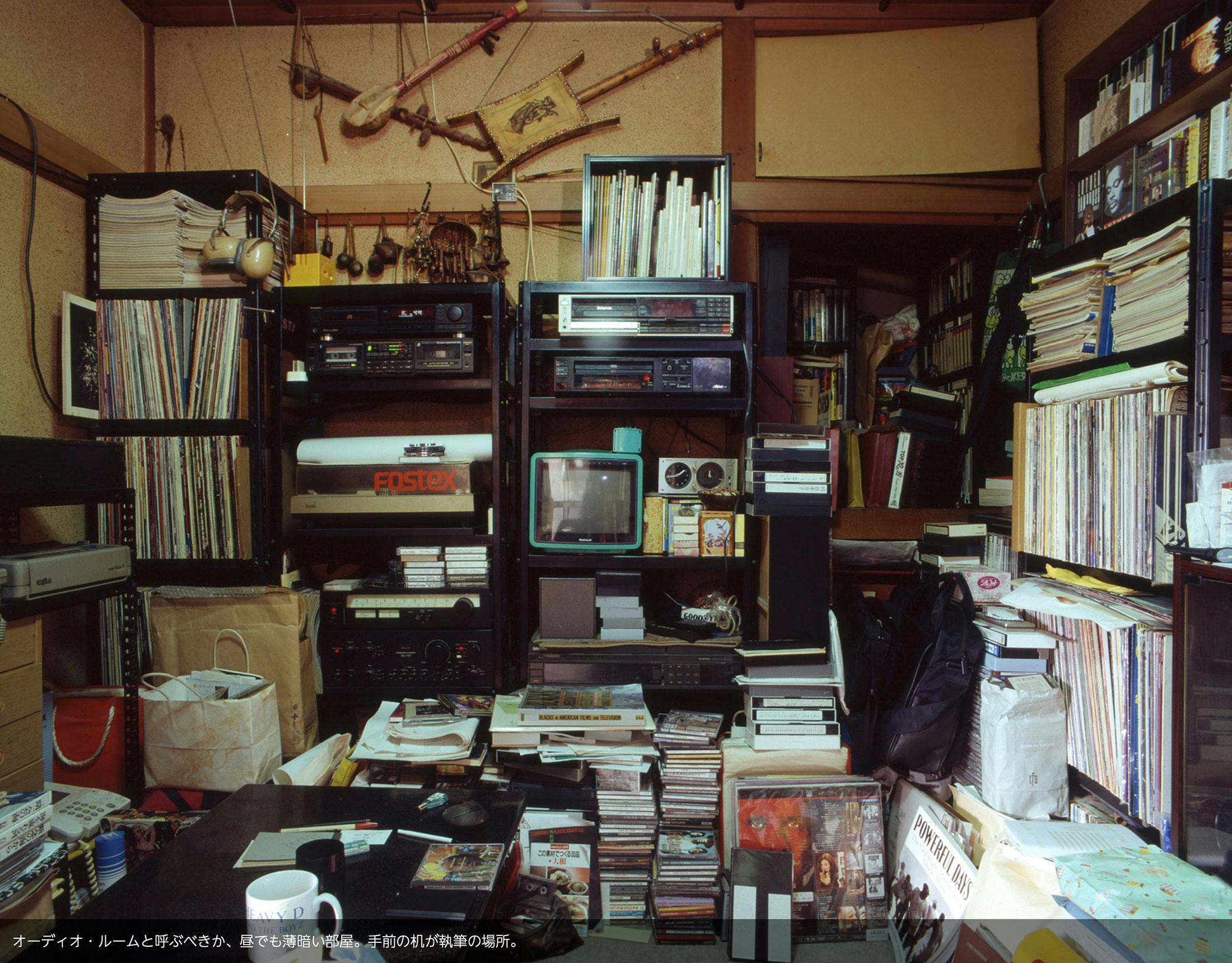

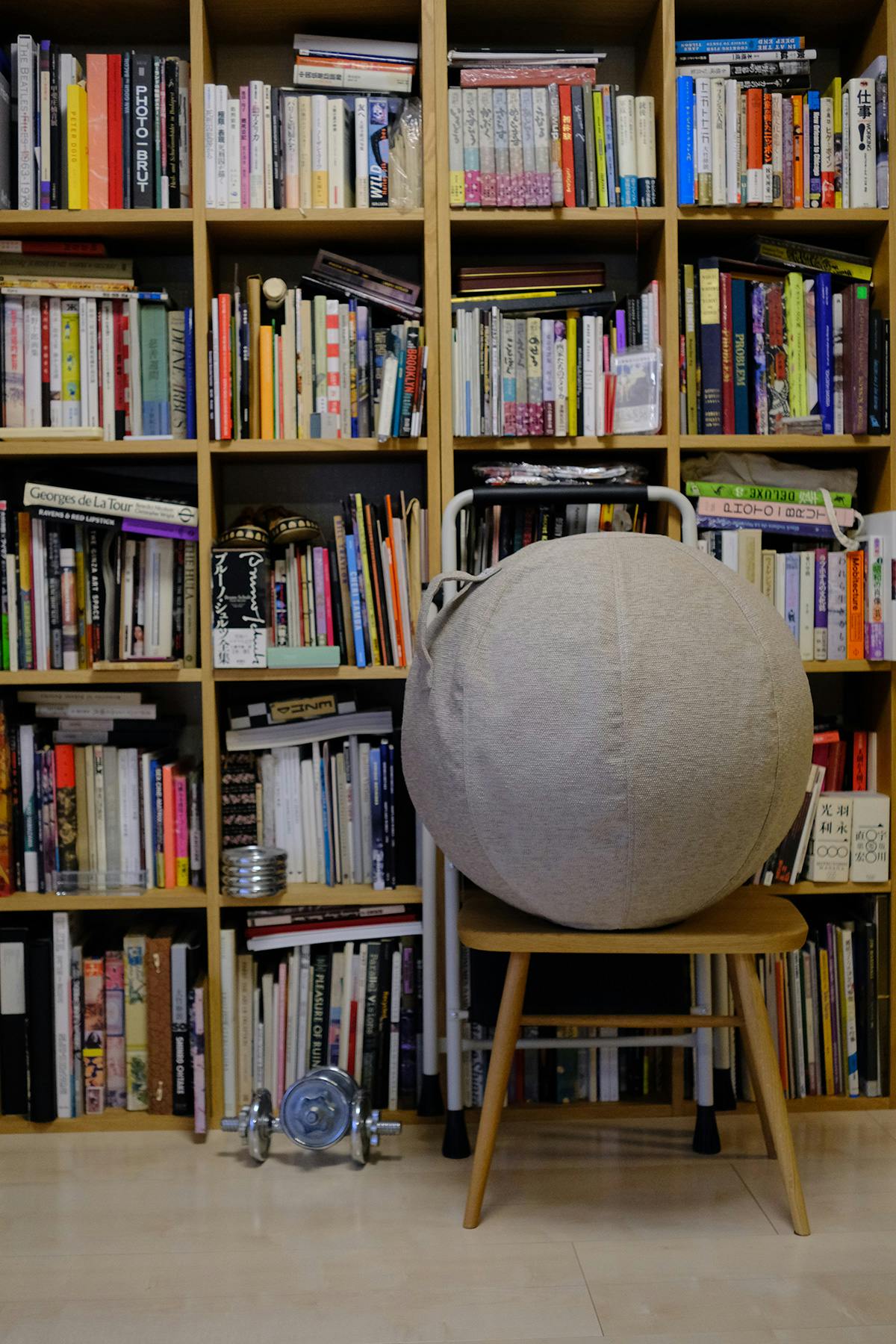

K_ I made "TOKYO STYLE" around in the bubble economic period, which was in the 80s and 90s. Somehow, I became friends with a lot of young people who live and work in Tokyo. A few of us decided to have dinner together, and they invited me to have a drink in their small apartment because they didn't have much money, and it felt really comfortable. There has been a lot of negative press about how Japanese people live in really small spaces called rabbit homes or whatever, but I found this comfortable to live in. They were so cheap, it's still cheap in Tokyo. You can find a six-tatami room around here, and payment is like 300 euros. In New York, what would the state of the place be if you found an apartment that cheap? I found there is a different kind of lovely way of living in this mega city.

At first, I wanted to make a story for some other thing because I couldn't take photos. So I went to lots of magazines to propose it, but everyone said no. So then I went to buy the set of large format cameras because I wanted to photograph the small places from a really respected point of view, just like an Architectural Digest photo.

With the camera, I started to photograph lots of young people's places, and it was much easier than I expected. Once, I helped to make a book of beautiful Japanese houses owned by rich people. It was so hard to make it because the owners were defensive and didn’t easily trust us to take the photos. Whereas the young people were so open with their apartments

How did you find the people? And how did you build trust in that? They allow you to not only photograph their homes, but sometimes they don't clean it up.

K_ If they are poor and young, they are so open, and I had no trouble with them. I started to shoot some places I knew, and I asked them, "Do you know someone around here who lives in the same kind of environment?" and they’d say, "Yeah, next door, I know him"—this kind of attitude. I would also ask them before I take photos to try not to clean. But they couldn’t clean it up even if they wanted to because there was no place to hide all of their things. Cleaning is an expensive way of hiding your personality because if you have a nice walk closet, you can hide anything. So living in a small space with a small amount of money is like an exhibition of your personality for private life.

Did you ever see the apartments before you showed up to photograph them? Or did you just accept whatever?

K_ Most of them, I just showed up with my camera the first time. I put most of the photos I took in the book because, in the end, you cannot choose whether the apartment is nice or not.

How do you approach projects? Do you do a lot of research or more organic?

K_ No research; that’s boring. It's just much nicer to let things just happen.

Are there any identifying nuances in contemporary everyday Japanese interiors?

K_ After I published TOKYO STYLE, I kept on photographing those small rooms for some time, and I made some exhibitions throughout Europe, Canada, Mexico and lots of places. Before doing that, I expected they would say, "Why are Japanese people living in these small rooms? I can't believe it." But most of the time, the reaction was, "Oh, I used to live in something similar", especially in Europe. This was a big surprise. Sometimes, I make books which are supposed to be very “Japanese”, but when I bring them overseas, the [foreign] people relate. So that's when I realised that we are, in the end, all living in the same kind of environment, whether it be Tokyo, Paris, London, New York or wherever.

I published "Happy Victims", which is a collection of photos of crazy young people spending lots of money on fashion. I found those people true friends. First of all, it was a regular article in a big fashion magazine. So I thought it was good for advertisement for the fashion brands press, but they were so angry [with the photos], and sometimes they threatened us with "We will sue you". If young people introduce their clothes which are from big fashion brands, then they [the brands] are not always so cooperative with publishing it. Brands try to keep their image branded in a certain way.

After seven to eight years of work, we finally published the book and had exhibitions in the U.S. and Europe.

Then, we had the same reaction as we did with the book TOKYO STYLE. Originally, I thought that young Japanese people buying expensive fashion brands was so stupid. Although, actually, Paris kids are the same.

We always have the same kind of image that the media wants to create. But actually, people are living in the same kind of way everywhere.

Did you do these kinds of collections outside of Japan?

K_ I did it in Shanghai. It's not the book, but it's a magazine project, and I also had a small exhibition just before COVID. That was very good because, you know, in China, they have such small apartments, but it's so much more expensive than in Tokyo.

It would be interesting to see how all different countries live in these small spaces.

K_ I think so, but now you don't feel much different because all of us know. People wear the same clothes like Uniqlo or Zara, and all of us have iPhones. So there is not much difference now compared to twenty years ago.

You curated an exhibition about Mom Art, one thousand pieces by twenty Moms. Do you think there is much difference between crafts and high-end contemporary art?

K_ Yes, I think so. Don’t you think so? [laughs]

I have been trying to find a nice mom's art for more than ten years. And finally held the exhibition and made the book.

What was your favourite, or what was the most surprising and impressive “Mom's Art” that you found?

K_ For example, those origami – we call them block origami. You make a small piece of paper like this and then make it into a triangular shape to create any kind of image. Mainly, it's used by older people to get to rehabilitation for avoiding stroke. But it's fun. And we met so many old people in Japan who are doing that, and they are amazing.

This is way more interesting than the Mom Art in the US.

K_ Well, I think I'm trying to find the same kind of Mom Art everywhere. When I was travelling around by car, I saw a lot of puppet faces made with socks. They are not good quality, but when you photograph them, they look like contemporary art.

How did they feel when you wanted to feature them? How did they react?

K_ They were just pleased but never thought they were artists.

I think that's interesting because nobody talks about it. And that's what I love about your work. You always touch on topics that may be obvious and are right in front of your face, but nobody talks about it or shows it in this respectful way.

K_ Every time I met a “Mom” artist whose work I was obsessed with, as soon as I wanted to buy their work, they would say, "No, no, no, we don't make it for sale," but they would give pieces to me. So most of the time you can't buy it, but they give you. They make the same things over and over again, and they give them to friends in the neighbourhood, and the people are pleased with the gift. That's what they want. It's not to make money at all.

That is what I like; it's totally different from the field of Contemporary Art. That's why we don't see it.

Being a journalist consists of two things: one is to go to a faraway place which cannot be easily reached, like the deep forest, moon or whatever, and to go meet someone inaccessible to the general public, or there's another kind of journalist, I think, which is so close to their subjects that most people don't see it. Like TOKYO STYLE, everyone, even the editors of huge Architecture Magazines, lives in small apartments with lots of objects. But they never tell you the story because it's too close. So, I became the second type of journalist.

You were also the editor of the cult culture magazines Popeye and Brutus. Were you able to inject some of your interests and sensibility towards more interesting yet ordinary aspects of Japanese life, culture and style during your time there?

K_ No, I don't think so. Because that was my twenties, I was much more fascinated by special things and places, places you cannot just go. There was a time of digesting, and then I started this.

Do you think that if you were an editor of a magazine, now do you think any of them would allow you to do it?

K_ No. When I made TOKYO STYLE, some people liked it, but no one followed the same path. And these Moms Art and Happy Victims things, too. In the fashion industry, people say it's fun, but they never wanted to cover it for real.

I don't want to flatter myself and say I'm anything like you, but you've certainly impacted my career, and I try to approach my work in a similar way to you because that's what I find interesting.

And you have Roadsiders, your weekly newsletter. Have you ever thought about making it into a print magazine?

K_ When we started in 2001, we wanted to make a print magazine but didn’t have enough money. So I had to start it on the Internet.

More than twenty years passed, and I started to realise a different way of making stories. If I make one story about your website, for instance, or of a film with a four-page story, I have to think about how much I need to write, even if I have thousands of words in mind to tell this story. Also, I have to think about which photos to put, which may be limited to only four [for instance]. That's the fun part of making a printed magazine, but if you make a web magazine, it’s totally limitless. We can write thousands of words every week.

I can include as much information from each interview as possible. So, I don't think much about the format of “published stories”; I want to put as much information as I have.

How do you decide what you're going to feature and write about?

K_ I found an interesting exhibition which will close next week. It takes two days to write, photograph and publish. I can do this thanks to the internet making the information supply faster.

Your book, ROADSIDE JAPAN, is one of my favourites. How did you find these interesting places to photograph? I read that you once met a man working in an antigravity laboratory for over twenty years.

K_ It was a pre-internet period. Now, it's easy because there are a lot of websites, and you find most of the things on Instagram, but in pre-internet days, all the information I had was just the road map. And it was film days, not even digital ones. So I put all the equipment and films in my car and then just drove around with a roadmap by myself with no research. I started by talking with local people like Ryokan staff and asking them, “What kind of interesting place do you have in mind around the area?”. And they told me some places which are written in the ROADSIDE JAPAN book. Also, just driving around and staying at small business hotels, most of the time, they have a small brochure of local attractions. So I picked them up and tried to drive there. Nine places out of ten are boring, but one place will be special. Sometimes, in the middle of driving, I would find somewhere from a sign on the highway. It was fun; we cannot find the same kind of excitement now because of the abundance of information. You couldn’t visit everything you’d discover online if you had all your life. After that, I wrote a book called ROADSIDE USA. I explored the country without a researcher, just by myself, over the course of seven or eight years. So it took a lot of time, but it was fun.

Which part is the weirdest in the U.S.?

K_ There is a lot of ‘Outsider Art’ in West Virginia, California and Wisconsin — so many interesting and weird people. There is a serious guy who is trying to make a huge time-travelling machine. Also, there is one of the biggest factories there, which makes plastic objects, like chickens, which are used for restaurant signs.

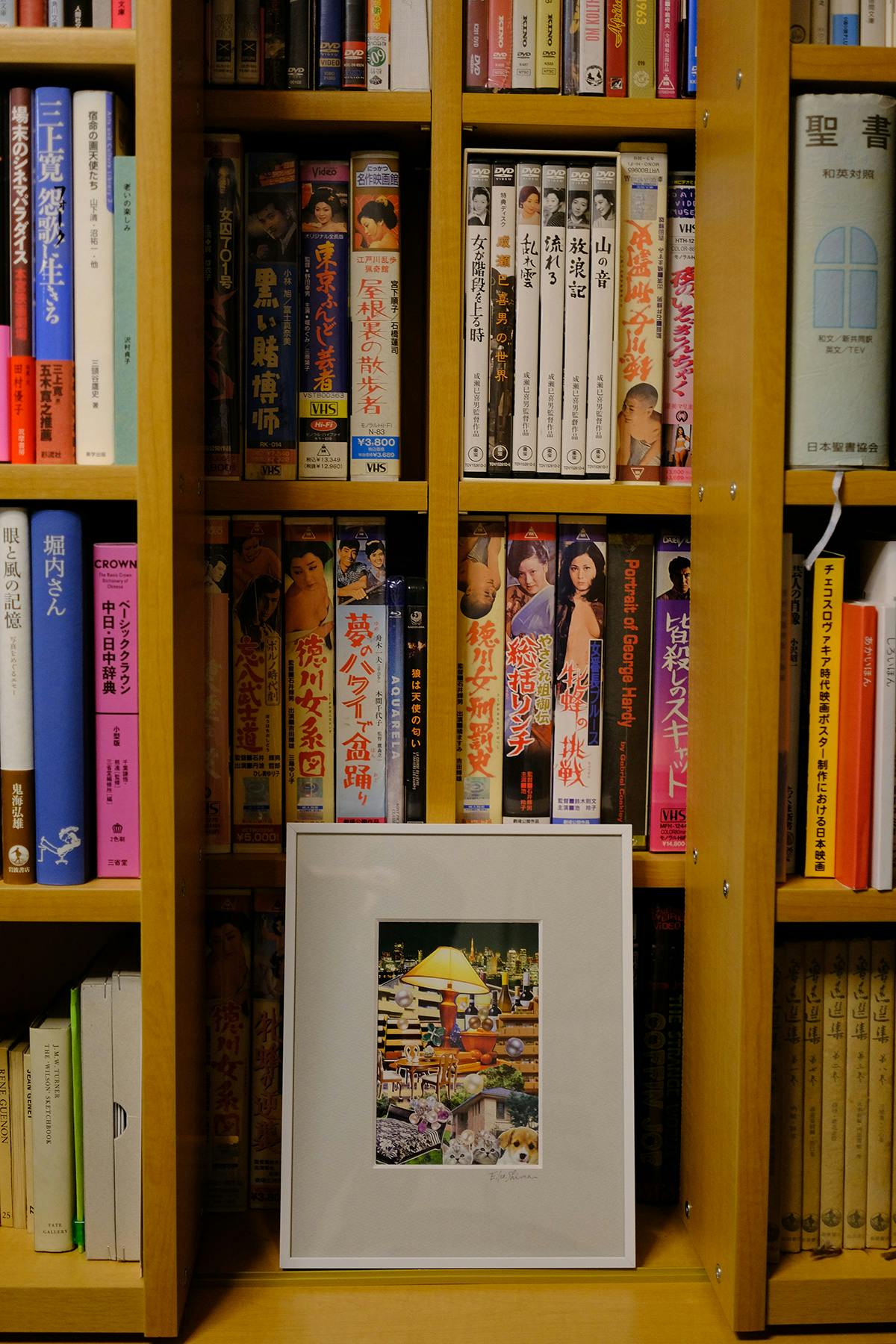

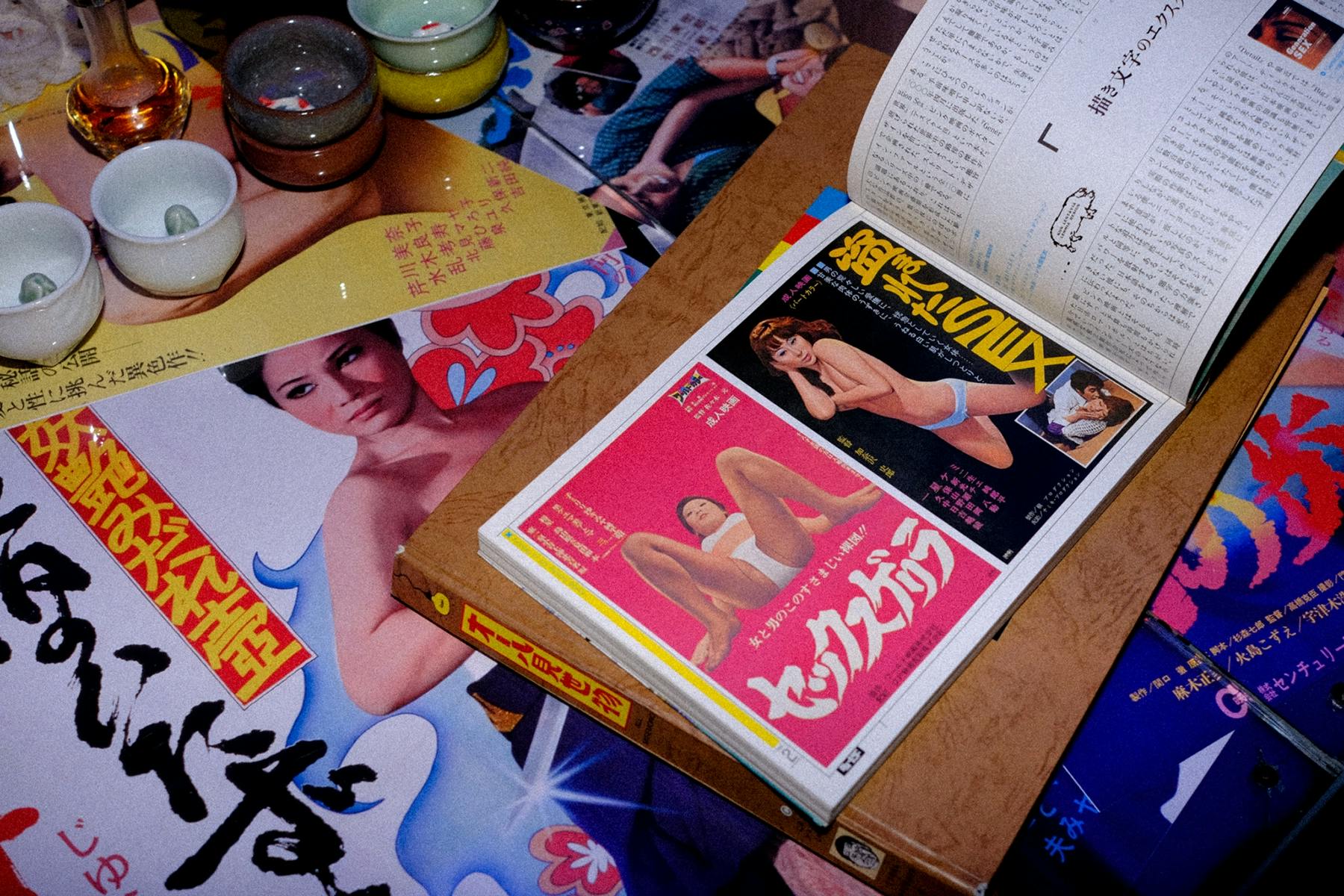

America has fun places, but Japanese ones are more crazy places. Here, sex is open, like there are Sex Museums or something, for instance.

Japan has a very creative approach to eroticism, which has both piqued interest in the Western world and provoked some more morally stubborn people.

How has this aspect of culture inspired projects of yours?

K_ There used to be many Sex Museums, but that was a roadside attraction. They tried to pitch it as educational, anthropological or artistic. But Japanese people want purely recreational attractions with crazy ideas. Actually, the main customers [of the Sex Museums] are women's groups, which went on bus trips thirty to forty years ago. So they go on a trip to an onsen, a famous shrine and a Sex Museum. Sexual culture is much more open in Japanese history because of religion. Unlike Christians, Buddhists are more open to having sex.

I was interested in how sex was shown in museum installations, and I also collected old porn movies and posters. They had small budgets, so they didn't hire a graphic designer to make their posters. They sent titles and names of the actresses and a couple of photos to the local printer who just fabricated them. That was such an easy job. There was no sense of real graphic design, but the poster design was the best, in my opinion. There are so many creative fields made by broke yet motivated people. Sometimes, the things they made were much simpler but much more energetic and imaginative than the ones by professionals. So sometimes I think, why do we need education? There are some local kids who don't think much about anything but just write. That’s the way I do it.

And that you said once that there are two types of artists. One is boring but receives lots of money to do what they want. Two, interesting but can't make money. But then, how did those people succeed? And what does success mean?

K_ It came out of when I was working in magazines when I was in my twenties. I saw many artists in New York, London or Paris who used to be famous graphic designers and then turned into mediocre artists who stopped doing commercial work. I could not believe that, but they were so happy despite not earning much money. I wanted to know their driving force. I like those people because of their energy, not the work. Making money is not bad in any way, but I was so interested in what force was strong enough to make a person forget that.

How did you balance following your passions, being able to eat, have a nice house and survive?

K_ So many stories about nice artists and famous people. I don't have to do that because a lot already exists. There are so many poor artists whose work is not good, but they are so happy. No press at all. So I want to make a balance in a way. I'm not saying this one way of life is better than the other because I'm only thinking about the young people; I'm not the one who tells them you have to go to the art field and forget about money. I want to give them a choice.

You can think about art as a means of making money, and that is not bad. If I show many examples, young people can choose, but if they only see some TV shows, magazines and books which only show “successful” people, they feel discouraged. And if I show a nice example of living in a small apartment and having a happy life making art but with no money, they can choose. I'm not a critic but a journalist, giving them many examples.

What is next?

K_ Recently, I republished my books digitally. We made huge PDFs of data. I already have ten books out. Some physical books are already sold out, and some publishers have closed, so I wanted to do an E-book project. I wanted to make them accessible around the world, not like on Amazon or iBooks. Also, I can put many images with high resolution, which I had to delete when I made books.