Studio Visit with Seetal Solanki

We visit the London home of Materials Translator, Seetal Solanki

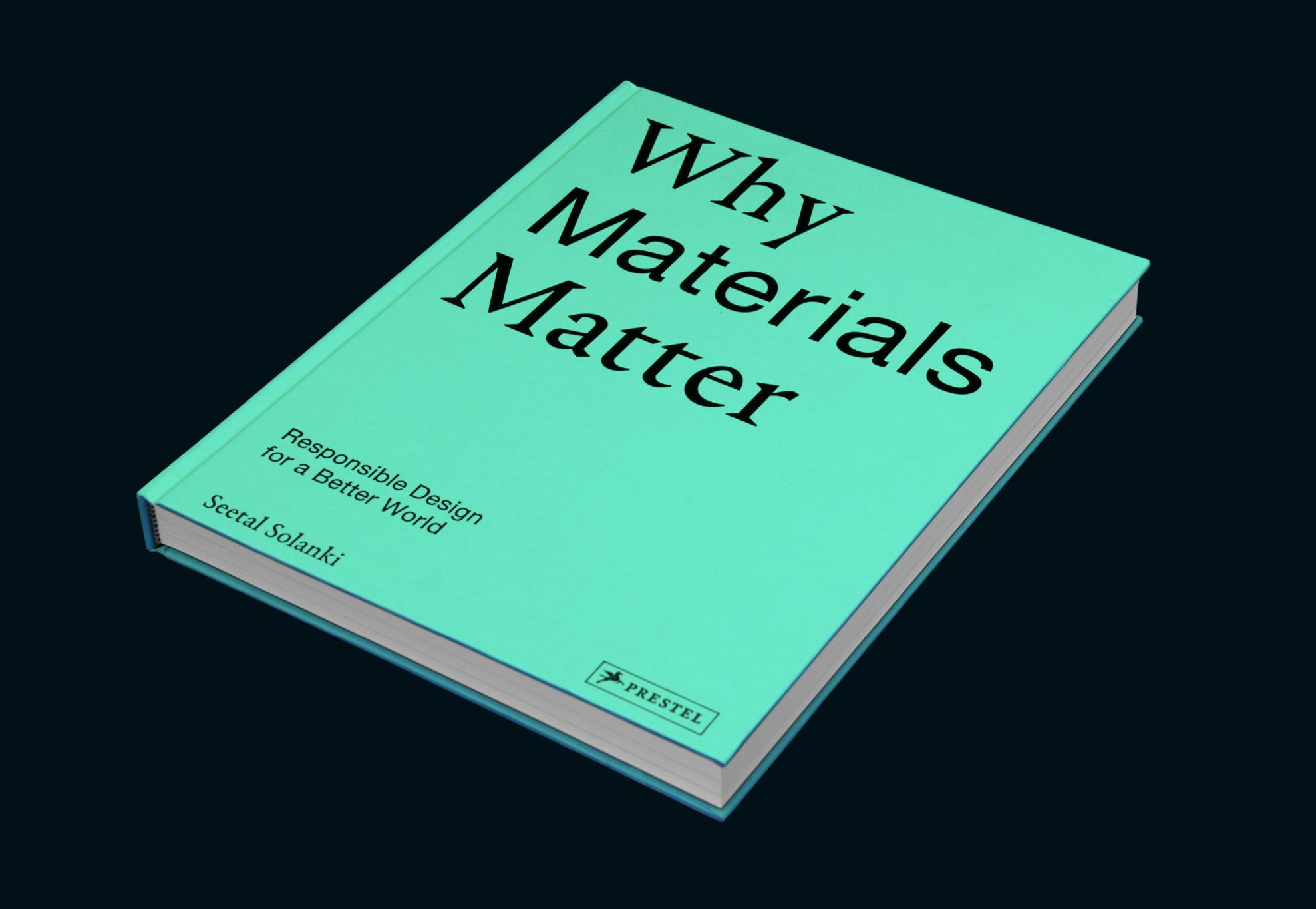

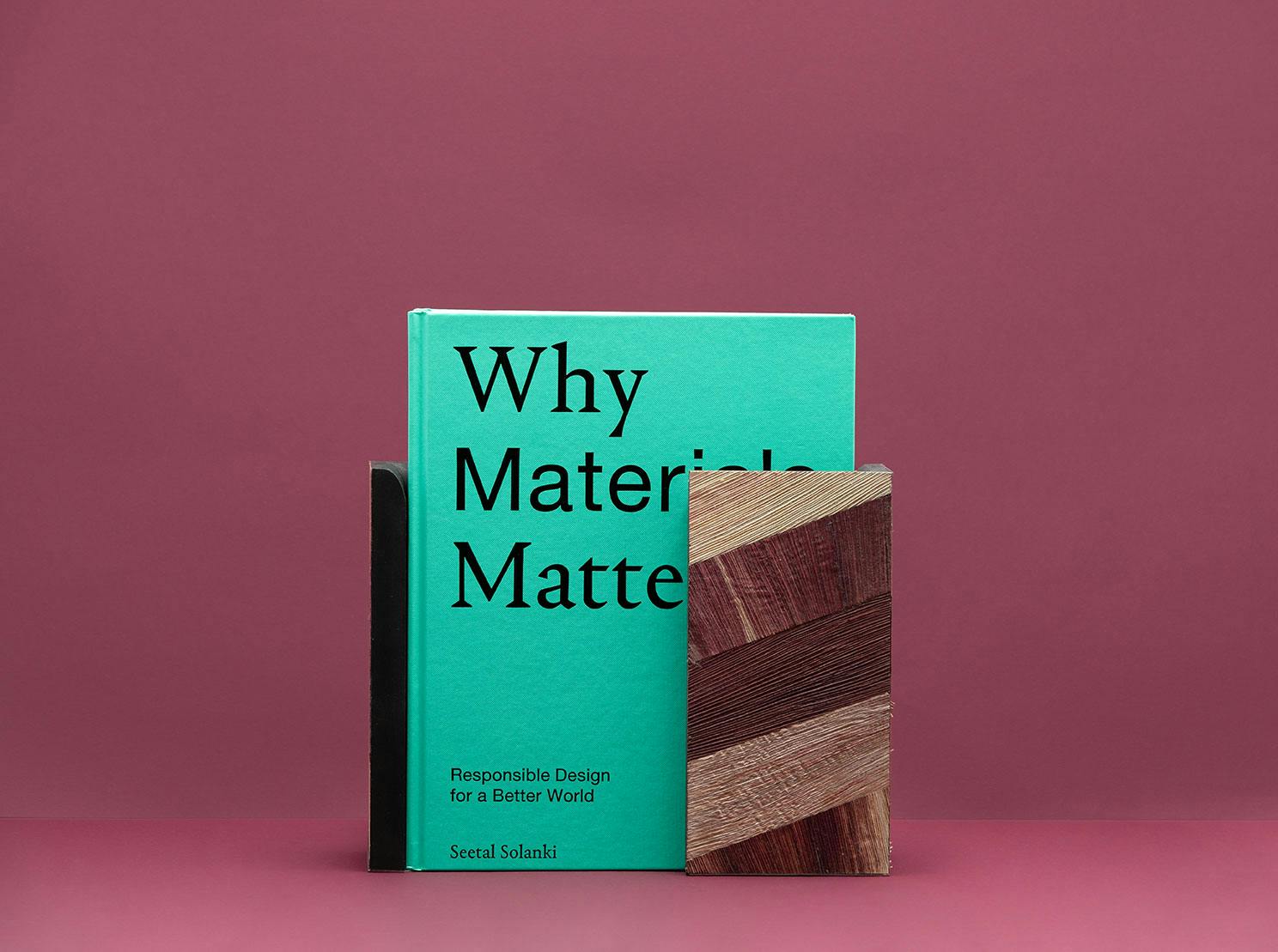

The first time I met Materials Translator Seetal Solanki in 2018, we were aptly sat around a defunct quarry-cum-contemporary swimming hole in a forest, several hours outside of Bratislava, Slovakia, for a week-long Design Symposium. "A Materials What?" I asked myself. Fairly new to the design industry at the time, I hadn't the slightest idea of the depth of possibilities materials held and the ways in which designers could experiment and navigate their practices around them. Soon after the trip, I bought Seetal's book "Why Materials Matter: Responsible Design for a Better World", which transformed the way I look at, approach, appreciate and curate design to this day.

Solanki's foundation in materials began with textiles and jewellery, refined through her studies at Central Saint Martins and Loughborough University. Yet, her earliest education came in her mother's kitchen, where she absorbed the ethos that nothing is without value—a sensibility that continues to shape her work. From collaborating with fashion luminaries like Alexander McQueen, Hussein Chalayan, and Prada to reimagining the use of local materials in projects like Potato Head's hotel in Bali, Seetal's practice is a deliberate intersection of craft, culture, and environmental consciousness.

Founder of Ma-tt-er, Solanki, is on a mission to teach us how to relate to materials—how they've traversed lands, shaped societies, and can inspire sustainable futures. She shows us that we should not approach materials as mere tools or commodities but as cultural storytellers, historical nomads, and vessels of meaning.

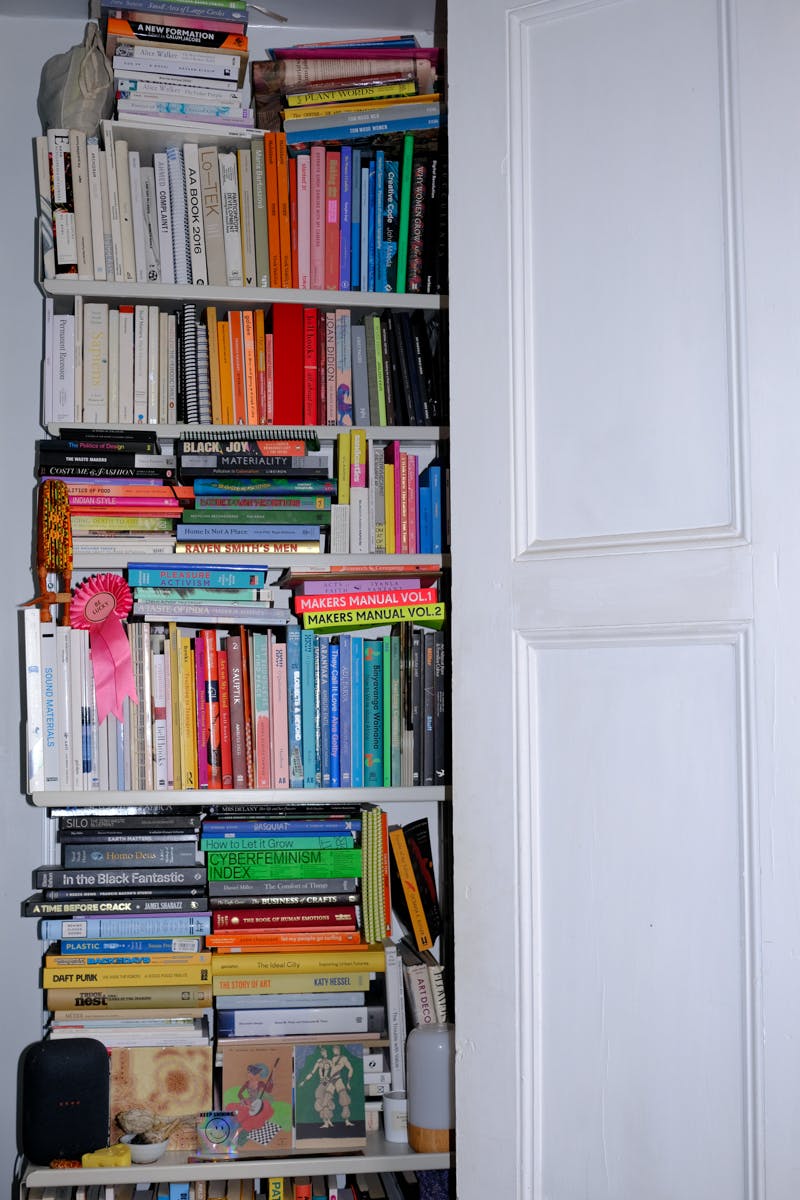

We sit down for a cup of tea in Seetal's London living room to discuss exploring the Material Library of various landscapes and cultures and how designers can make a social impact through material exploration and running a multidisciplinary creative practice without borders.

I first learned about your company Ma-tt-er when we met at a design symposium in Slovakia swimming in a quarry. Your book Why Materials Matter came out during the London Design Festival about a month later. Can you tell us a bit about Ma-tt-er?

Ma-tt-er is a practice where people can learn about how to relate to materials and how materials have migrated across different lands. We guide people to apply that to the practice of it.

And what kind of projects do you do? How do you apply it?

I trained as a textile designer and did a master's at Central Saint Martins called Textile Futures before doing Multimedia Textiles. I also did jewellery and silversmithing at Loughborough University. But I would say cooking was my introduction, learning how to cook through observation with my mum. I was taught at a very young age that everything is precious and has value. Nothing was wasted, everything felt meaningful.

I applied that belief system and fundamental principles with informal and formal learning in a practical yet also philosophical way.

After graduating I looked to understand how the industry works and fashion was my main go-to. I've worked with Alexander McQueen, Hussein Chalayan, Chloe, Missoni, Prada and even high street stuff. It taught me a lot about how things are made.

At that time you were working more in textiles, right?

Yes, I went on to do automotive as well, so car interiors and architecture, lighting installations you name it, I've tried it.

I worked for thirteen years before creating Ma-tt-er. I was just getting frustrated with the whole system with design and processes only shoehorning in materials at the end.

So you could help a brand rethink how they approach their process?

Yes, for example, Potato Head in Bali invited me to understand how to build their hotel using local materials. It's the most meaningful project I have ever worked on to date, comprising 170 rooms, loads of public areas and restaurants.

Did you have to build a material library or did somebody have one for you to look through?

They already had a lot available because they had already built a hotel. But we went on field trips as I wanted to learn about the craftspeople and the materials they were working with, such as bamboo, teak, ceramics, and lava stone, and meet the glass makers and weavers, natural dyers and look into plastic recycling furniture.

The materiality of the island was so eye-opening and a massive catalyst for understanding how we can process those materials to offer different kinds of functionalities and provide a real sense of where you are.

Tourism in Bali is booming, but many of the hotels are very generic. The brief was to offer a sense of place with spiritual elements, understanding the balance between the demons and the gods as Balinese people place offerings for the gods and demons. For any materials that we were taking from the island, we would always be giving something back.

A lot of the crafts were fading as the craft people's skills were being harnessed just for tourist products. We worked with Max Lamb and Faye Toogood, as well as Dirk Van Der Kooij, who were paired with different craftspeople to create amazing pieces of furniture, installations, and interiors.

You're quite the multidisciplinary, renaissance woman, curating, writing, and running Ma-tt-er. How do you define yourself?

I describe myself as a materials translator. So, it's taken me a long while to get to this point, but I, describing myself as a designer didn't really do it for me. I was very uncomfortable with the title as the craftspeople in Bali were bowing down to me while I considered them to be the true masters of their material.

I'm more of a generalist and just want to have a peer-to-peer conversation with craftspeople. As I work so internationally, I was just like, I need something else that helps me navigate that a bit more seamlessly yet also invokes curiosity

How can a young designer make an impact and why is it important to consider the materials?

Take the example of Dushyant and Priyanka from Raw Material who work with disused marble in their design studio in Rajasthan, India.

The people who mine for the marble normally carve white, purist marble for Hindu temples. They find beauty and purpose within those offcuts to create pieces of furniture and housing. There's still so much worth, value and integrity in every single material that has been excavated from that land. They keep it within an ecosystem which makes sense without scaling it because they understand what it means for them and the community that they work with.

I'm hoping that by bringing some kind of awareness, but also guidance towards another way of making and producing with materials and consuming, it can get people to think and make differently.

In another interview you were talking about the importance of living consciously, but also not in such an extreme way that you wouldn’t be able to keep up with it. How is it possible for a global industry to change in that way?

I'm a very hopeful person, and I believe that change is with us. There's a will to want to change. And I think it's about starting small and in a manageable way. Why do we need to turn things upside down overnight? It doesn't work.

So, it's about giving people the guidance to produce global products in certain places where those materials exist. The onus shouldn't just be on the material, and the material isn't going to save the whole world. You have to understand how to design and produce.

What about the discussion of price? How do you think it's possible to change mindsets that are so conditioned by fast fashion brands and other big online retailers, and the idea that doing things more consciously is going to be more expensive?

I don't believe that at all because I feel like this survival mentality is all within us and we need to know how to survive on a shoestring.

Cost was always an issue in our house, reusing was just the way that we would operate. So the cost is the time to rethink and rewire, but it was common sense at the same time. It just wasn’t labelled sustainability. It's just the way that we live.

So it's more about education and rewiring than anything else?

Yes because everything is available to us but a lot of the time we think that a new solution or a new material is going to save us.

Julia Watson’s Lo-Tek talks of going back to many Indigenous practices, methodologies and systems that are not extractive or destructive. We're always thinking about creating the next thing, which creates problems that we can't anticipate. And then we have to fix those.

Yeah, which is why I don't believe in solutions. Why don't we just aim for alternatives rather than solutions, recontextualising, offering another approach to doing something rather than letting it be someone else's problem?

When Central St. Martin's launched the program Material Futures, what type of impact did that make?

I did it from 2005 to 2007 when it was Textile Futures. It’s changed its name to Material Futures since. The idea of broadening a course is useful because of all the strands that encompass it: there's a science, engineering, humanitarian, social and political side to it. So I think relabeling it allowed more people to think outside the design industry. It meant that you could meet scientists, geologists and agriculture. We all need to work together.

Textiles perhaps felt very limited to fabric. I wrote this piece called ‘Textiles Are for Girls and Materials Are for Boys’. And it shone a light on how people perceive textiles to be very domestic in their orientation and positioning. When people would ask me ‘What do you do?’ And I’d say I'm a textile designer, the automatic response would be, ‘Can you make me a dress?’

Sure, I can do that, but I can also make a textile that could power your home. And so the misinterpretation would be very apparent. If I was to say,’ I work with materials. I'm a designer. They’d automatically think I'm an engineer, it feels more solid.

Talking to different designers that were doing new material development, they didn't necessarily know a scientist or an engineer, people that would know either how to scale this material, make it durable, or safe for eating or drinking in for example. How can a designer collaborate with these different people?

We don't get taught these things in design school at all. So, we have to think about it from another perspective. Who is that person who tests or understands the science behind these materials? And where does that get made and produced? We would have to approach different kinds of institutions that have this knowledge and research available to them. But it's a foreign language.

Are there any resources or do you have an index?

It's really difficult because there's a lot of gatekeeping in design, especially in a city like London. Whereas in India everything happens outside. Even in Lagos, everything spills out onto the streets and the visibility of someone making something is open. You might not be able to approach them just like that, but you know where they are. Whereas here there's no understanding of where this exists, even though it’s a place with industry.

But it doesn't mean it shouldn't exist here. It just means that there's a cost for it to happen. Take the way Fernando Laposse is working in Mexico. His intention is very different to something like a food-safe product. That's why the intention and the purpose are really important to understand. His intention is to keep an Indigenous community and land alive so that they can all live together and be able to build something that continues that lifeline.

So it's not just sustainable but regenerative.

Yeah, I find it difficult to know what the difference is. I'm struggling with the definitions at the moment, I will say.

He tells me about it in the context, it's not just sustaining, they're replanting and rebuilding further so that the next generation will have even more. They were growing this corn to eat but also sold the husks as architectural veneer.

He had to go back to the source, seed banks, farmers, and agriculturists, so he could understand how to work, regrow and replant. His way of collaborating is to start from the soil. To have that knowledge you need to speak to the people who have access to this, working with communities that farm the land but also different designers, sociologists and anthropologists as well as political activists. It's very far and wide but that's the impact a material has and that's why the intention is really important to understand from the get-go. Otherwise, there’s no purpose.

He's even said ‘I don't want to grow’. Because if he tried to scale it, he might not be able to sustain the first community. I think it's just a way of thinking that can be applied in so many different countries in different ways.

It starts from that. It doesn't need to be this one thing.

You're also a senior researcher at On Road agency, helping brands in a new way.

This is a more recent endeavour. Ma.tt.er is more my artistic practice and OnRoad is a way to engage with brands. I'm able to tap into what means a lot to me, people, researching how culture moves, what culture is now with a younger generation, and how those generational shifts are making an impact on brands because a lot of the time they might be missing the mark.

We research and offer cultural insights on behavioural shifts in a way that’s not exploitative. So we work with people like Nike, YouTube, Spotify, Depop, and BBC and tap into the communities and subcultures that we want to foster and nurture to allow those voices to be heard and maybe even trained.

The other side of my job is to understand and create more of a public-facing arm for OnRoad to nurture the talent internally. I feel we don't necessarily learn these skills in school and not all of us have the opportunity to go to higher education. And even then, they don't teach you the practical skills of how to deal with clients.

You've been a professor at RCA for a long time. You've also started a school in Lagos, and you've been a part of Make Your Own Masters. What do you think is missing today in education and what does the future of education look like?

Everything I do is centred around sharing, so learning is always present. I'm always going to be a student of materials as opposed to an expert because it's so endless. That curiosity is something that constantly drives me. But all these different spaces I've taught at CSM, the design academy, Eindhoven, are all very principled and formal, to the point where it became formulaic. And that's when I started to question the meaning of this formal education. Doing a Masters is a real privilege in the first place, but why does everyone end up doing similar projects? We're not really encouraging uniqueness. That's what a masters really is, positioning you where you are right now and you're doing that through your creative process. What change do you want to make and what change do you want to see? That’s what we should be getting the students to understand about themselves. I did formal education teaching for over ten years and got to understand those restrictions where every institution has a set of rules. But it's getting to a point where it's not facilitating home students and it's not facilitating that kind of growth to happen.

Make Your Own Masters was born out of that struggle. Stacey, the genius behind Make Your Own Masters and a beautiful person, decided to take it upon herself to create her own Masters, which meant that she had to understand and dissect the whole infrastructure of a university. So she had briefers, peers, mentors and so on.

How did Lagos happen?

I wanted to do something where my whole life changed basically. I had a lot of friends in Lagos and had the opportunity to do an artist residency there. I wanted to be a maker again, to feel free again. The residency was with 16by16 in a design-led guest house/space called Plan B. I ended up being there for 18 months during lockdown.

We wanted to offer learning through materials and did a whole series of workshops with the community that lives on Ajasa Street, in Lagos Island, which is probably one of my favourite places in Lagos. Everything just happens outside, and so understanding what the people needed on that street gave us the ammunition to understand what the space could be for them. Plastic was blocking all the sewage systems and plumbing, so we created a whole workshop where we had different stations to recycle plastic and make different products using familiar domestic tools, melting, shredding, and blending the plastic bottles we got through a collection facility outside of the building.

Everybody got involved, and we offered some training on the use of certain tools and machinery. But we also made our lighting, bedding, and insulation for that space.

Just from the materials found in that area?

Yeah, and the markets available. Coconut, corn husks, hibiscus, indigo dye, all these different ropes and laces that were being discarded, plastic. There are artist residency spaces above, so people come and stay there, and work. It’s a community centre. On one side, there's a woodworking and plastic recycling workshop, an urban farm outside and upstairs is where artists live.

We hosted dinners and set up a fermentation lab, so it's all applied research and learning, and that's what I mean by design thinking and doing. You need to take action, and that's what's really missing in education right now. So this is an alternative. And the fact that it's growing without me being there is all I was hoping for.

So what's missing is the action and the doing. I don't want to just train thinkers.

I think that's such an important point to end on. In our industry, it feels very cerebral, which is very exciting in a lot of ways, too. But I do think that a lot of people get caught up in that, and there are a lot of missed opportunities.