Studio Visit with Max Radford

We visit the London, UK, studio of Designer and Gallerist Max Radford

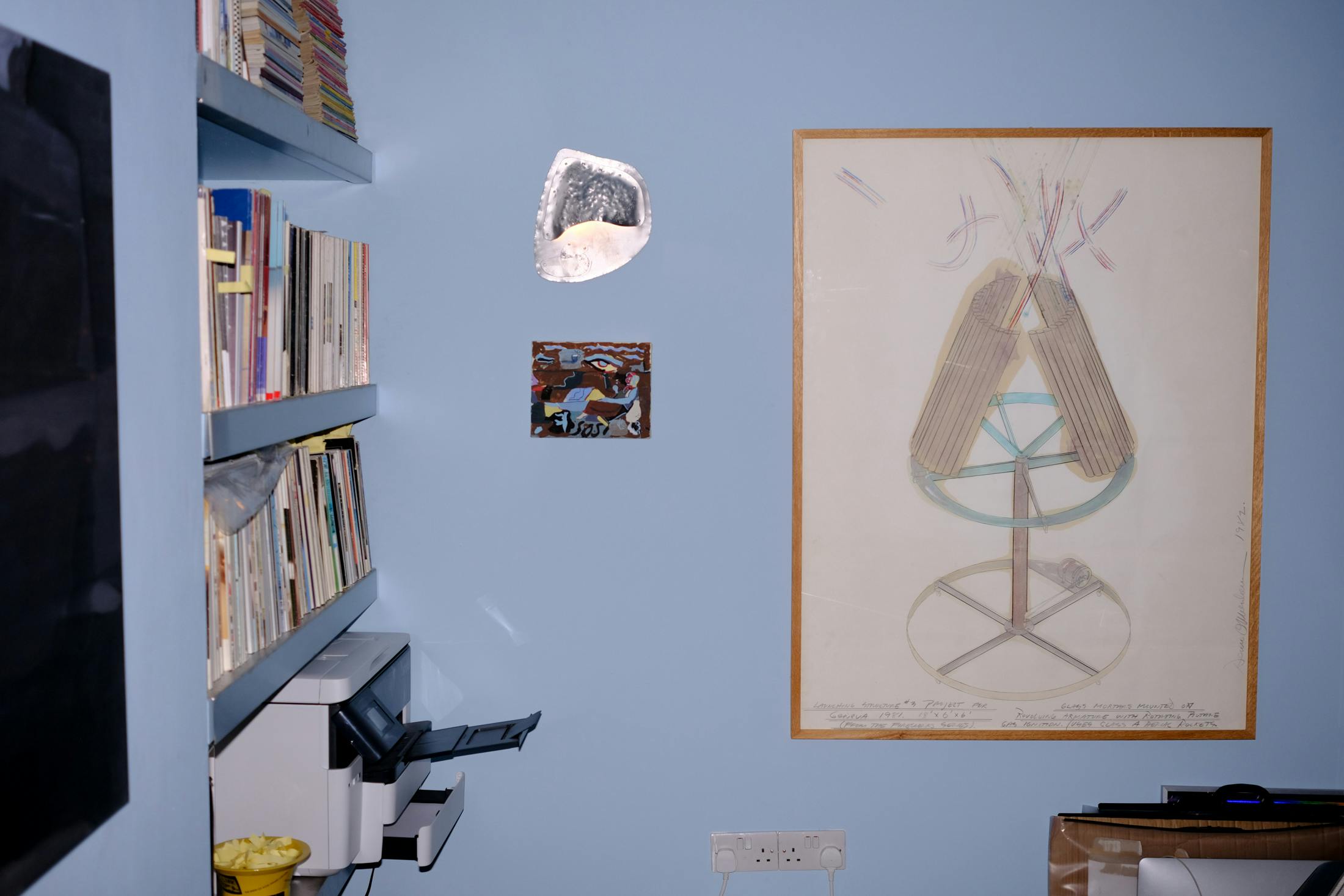

Entering Max's monochromatic baby blue duplex office under the overground in Shoreditch, East London, felt like walking into a late 1980s remix of a Georgian genie bottle – in the best way possible. I always find myself most comfortable in Monochromatic spaces, which have a "womb"-like effect, allowing your senses to recalibrate and focus on the objects and details within them. As Max prepared coffee, my eyes drifted over a sleek black leather sofa beneath an aged, rough-textured yellow art piece flanked by an angular '80s metal sculpture on one side and a lamp crafted from a rugged stone on the other. The space was a testament to Max's distinct, unexpected, yet deeply informed aesthetic.

An avid vintage interiors book and magazine collector and archivist, Interior Designer and Gallerist, Max Radford has developed a breadth of knowledge built on niche and rare references from the past, which inform his astute sensitivity to who is at the forefront of our generation's top design talent. Managing his time between his interior and set design practice and his eponymous gallery, he still makes time to meet with young designers regularly to give guidance and feedback. With The Max Radford Gallery, he commits himself to promoting the vanguard of London's emerging design scene, particularly interested in process-led artists.

Despite meeting him dozens of times prior, we never had the chance to really sit down and speak. Calm, curious, interested, passionate and deeply generous – the time flew by between trying to manage the interview with unavoidable interludes of two design nerds being led astray on side topics. We discuss everything from his investment into a rare vintage magazine collection to his evolution into interior design to what he looks for when looking for new designers to collaborate with in his gallery.

Kristen_ You're both a designer and a gallerist. How did you get started?

Max_ I studied fine art at Falmouth University in Cornwall as I wanted to do something creative. I interned for antiques dealer Max Rollitt and transitioned to interior design, drawing up all of the bespoke furniture and the fitted kitchens or rooms. I started buying lots of design books about early Georgian furniture, but also about 20th-century design and got a job in London with Hollie Bowden doing more contemporary work. I also designed a bar with some friends and got more requests following that.

How does that work when you're working for an interior designer? Do you have some kind of agreement that it won't be too close to theirs?

People will often end up getting jobs off the back of who they've worked for. But what I was doing was different to what Hollie's renowned for, being more high-end and luxury. She was very supportive of me working on my own. We're still mates now.

And how did you get your first job?

People reached out through Instagram. I was very lucky as I didn't have any photographs of anything I'd done apart from a few assembled sets. People see your stories and then ask you whether you want to do some projects. It feels different nowadays because the algorithm's changed so much. I'm struggling to continue to create the content that it wants to be able to grow. I feel like I've stagnated which doesn't bother me because outside of Instagram everything's fine.

I do a lot of research through secondhand books, it’s a passion we have in common. So how does that fit into your creative process and practice?

I've started picking it up again. I bought two cars full worth of magazines and started a Substack with references.

I used to buy a lot of records but just transitioned to spending that on books. I read an interview with Michael Bargo who said that he started his day with a coffee and looking through design books. So I'd buy all these books, look through them whilst I was having a coffee, take a nice square picture of them, and put it on Instagram. Now we've got A3 flatbed scanners, and we're looking through piles of magazines and books. It's become more of a job, but it's still very enjoyable researching quite specific periods and finding lots of stuff that you've never seen before.

That's one of the best things about old books. I think nowadays the algorithm across digital platforms really flattened what we get and all the interiors we see look the same. Fifteen years ago, the interiors had much more personality. But it's starting to come back.

Yeah, homogenised interiors, not touching on anything in particular or the different styles. They're very beautiful, but they don't have any character or soul.

Do you ever get worried about that with archiving?

Yeah, because you're then providing more fodder, in a way. So rather than putting all the research on Instagram, we now have it in a Substack, so it feels more like a newsletter that people are seeking out. It's an outlet where you can see stuff that you most likely haven't seen. Hopefully, we're providing weird and wild enough stuff that it's sort of desaturating the blandness.

What made you decide to make the Substack instead of Instagram?

We were very fortunate that the world's largest magazine collection was selling off lots of mad stuff. So we ended up having this insane collection of references, things that we hadn't seen before. It just felt like Instagram wasn't the right place to put it. We paid quite a lot of money for it. So it's just interesting to see whether or not other people would want to pay for access because you're offering a filtering service. We do two big posts a week, which is probably twenty magazines worth of stuff that we're going through. So far, I think we've got about 140 subscribers.

I like that there's a new platform that creatives can take into their own hands a bit more.

Yeah, exactly. And it's not full of advertising. The video content is allowing things to go back to a flatter media. I feel slightly guilty because it was established as a platform for writing and we're providing something that is not writing.

I think I'll probably make one for say hi to_ with courses for designers, how to deal with contracts, talk to lawyers, and add resources. You can gate it, and charge a little bit of money for tools or valuable resources.

You're really into ‘80s and ‘90s design. You’re finding a lot of functional art from that time. Can you tell me more about that?

The first stuff that inspired me was ‘80s and ‘90s German design by a group called Pentagon. Lots of steel and stone. And that stuff sort of started the hunt for it. Obviously, there's all that amazing Japanese design. It was just a question of trying to find more and more material references to try and work out what was going on there.

We started looking at Crafts magazine which opened up a whole new door. These magazines are pointing the spotlight on recently graduated people in sheds. You'll google them and the school they went to and you just can't find anything else about them but fleeting references to things, particularly from that period.

It feels like it’s a period where art and design were allowed to coexist and be themselves. It's like everything came a bit more design again in the late ‘90s and then in the early 2000s. So there was an interesting bubble there. But we're trying to find more stuff about the early-2000s design now, the stuff in the grey area. It’s quite difficult to find because it's either on websites that are slowly falling apart, or not actually on the internet.

Given the expanse of the internet, I find it harder and harder to do proper research. I do much better with books and magazines. But maybe that's good for us, I mean, for our practices as well.

We're very fortunate to be able to look at all this stuff because you can reach the end of the internet about design pretty quickly.

Would you ever write a book?

It’s something I've never thought of, but I love doing side-projects, so it'd be amazing to do a book about our favourite mad references and get in touch with all the original photographers.

What interests you most about the '80s and '90s is this kind of crossover. There was so much money, so there was more room to expand.

Materially things were a lot more interesting. Moving through early 20th-century modernism, the whole Scandinavian mid-century thing had happened, functional, considered furniture had been doing really well for sixty years by then. It allowed people to step outside of furniture having to be the most useful, versatile and practical thing because that had been so well covered and they were just able to do weird things.

And maybe push it, but there's always a rebellion right after each movement to do something new.

Exactly.

I’m also really drawn to ‘90s interiors; I think I feel more comfortable in spaces that remind me of when I was young. It’s nostalgic for me.

That's probably true. I have a not dissimilar thing with houses in England that feel old because I remember them as a kid.

Do you exclusively work with contemporary designers in your gallery or do you also have historic pieces?

We only work with London-based contemporary designers. It makes it easier to give yourself some parameters. Also, my interior design practice allows me to find weird ‘80s and ‘90s works for clients.

What made you decide to open the gallery? That's also kind of a big risk to take.

In the beginning, we did everything ourselves on a shoestring so it never felt like a risk. But as you grow a following, people expect things to be more polished, and then it starts to feel like more and more of a risk because you are investing more in each show. In the beginning, it was quite carefree and a laugh. It can end up growing at a ridiculous pace or you can just try and keep it quite lightweight instead.

I feel like there's so much pressure to keep getting bigger. You might lose the fun part and end up doing more of the managerial stuff and running the company.

I totally agree. You see that through working for other people. It opens up the question as to whether or not you want to do it that way or stay focused on the design and creative stuff.

It also gives you room to have other side projects.

Yeah, we started doing set designs as well, which is creatively rewarding.

And all your activities kind of feed each other. Which one of these takes the most of your time?

Interior design. But there's great chemistry with the gallery in that way as we work with lots of the designers, placing their work in interiors or commissioning them to do bespoke pieces.

But the gallery continues to take up more and more time in a very good way. It used to be one day a week and interiors were the other four or six in reality, but it’s closer to two days now. And the set design can be half a day.

We did a project for a German shoe brand. And then off the back of that, for a few other German brands but interiors can take a couple of years even though it’s very rewarding when they're done.

With the gallery, you’re planning a show but then it all disappears or ends up in the showroom. With the set design stuff, it's almost like a happy medium.

How do you attract the type of clients that you want?

We've just been lucky enough that people come in with an understanding of my style.

How do you decide what designers you work with?

I always have a look through all the portfolios and reply. If you like referencing and looking for furniture, it needs to feel like you've hunted for something.

We’re combing through social media and started working with more fine artists by going to London graduate shows. We get a lot of international applications from people but we just work with people from London.

We keep everything on record and we bear people in mind for future exhibitions. We're planning on holding an exhibition of non-UK-based designers and artists.

I feel like there's so much opacity in our entire industry.

People think design galleries are far bigger machines than they are because there's a website, branding and shows in interesting places. You just assume that these people are selling tons of work all the time but it's just like me and Anya Glik doing everything ourselves.

But you're investing so much, I think that's really important for the designers to understand.

I'm so keen to dispel any of that with younger designers as it’s maybe a little more complex and not as big and fancy and as full of money as you think it is as well.

Is there something specific you look for when you look for new designers to work with?

I find it most interesting when people have researched and developed their own processes and applied that research to domestic objects such as chairs and lights. Not everyone can create a new process, nor is that necessary, but that just seems to be like an underlying current.

Yeah, it feels like a red thread, having that depth. As a gallerist, you're kind of seeing into the future and also the longevity of that artist’s career. They need to have something that they've been developing aside from something that's a nice, shiny, photographable object, right?

That's exactly it. We've seen that happen over our four-year existence.

It’s something we talked about earlier this month with Shawn Adams from Poor Collective, about what people are now doing with designs. I think lots of stuff in terms of form and design has been explored as much as it can be. There are no bad things. We're now looking back and doing things in new ways with new approaches, using design to talk about something else. It’s far more interesting to be looking into it as a gallerist.

And it's particularly inspired by Kim Mupangilaï's work. I think that's like a big touchpoint for a lot of people. It's an incredibly beautiful, collectable Instagram-worthy design on its own. But then when you understand her personal and family history it makes it more interesting.

She's such a great example, you can see her work progressing as she explores her own identity, like a dialogue between her and the work.

It's not just the same thing over and over again.

How do you feel about designers who work with many different materials, but have a red thread of their vision or designers who choose one material and go with it?

I love the puritanical one-material approach. But if you've worked through enough and have a great understanding of your personal design practice, then you can still apply that to many different things and materials and Lewis Kemmenoe who we work with, does that very well. So you can see that his various collections of work progress or have different understandings. When we first started working with him, he was working with timber and veneers. And then he progressed to solid woods before working on aluminium pieces, always with a junction between each.

Kwangho Lee is a great example, with this knitted vinyl and work with bronze and enamel paint. Or Max Lamb, you always know it's them, but it's so hard to achieve at the same time.

Some people are just built to do that in some way and they do have that strong identity in whatever work they do. For them, it’s very intuitive but I wonder how designers can cultivate that because to have longevity, we need to see their vision through many different kinds of mediums and not get pigeonholed and plateau in one thing because when you do something that works you can get afraid to try other things.

Do you have a dream project or maybe something you're working on that you're excited about?

We mainly do residential projects which have been nice and we like working with people on their private homes but we're looking forward to starting commercial projects on a different scale. You get to work with commercial contractors who do things a lot more quickly. It feels a little bit more serious because there's more money at stake.

Also, it'd be nice to do interior projects in the States, particularly in New York.

I've been coming to London for a long time and I feel like there's a really strong design community here compared to other places. How has that changed after Brexit as a lot of people have left?

It's sort of almost galvanised everyone even more. So we're all in it, trying to ship our work around the world. So everyone's very supportive of that and like giving people the right shipping contacts and how to do all the crazy paperwork.

We all end up at the same shows, going to the same pubs before and afterwards. Whether it’s graduate shows or older people in the scene, everyone's just so keen to see and support as much of it as possible.

We work with people of all ages. But in terms of those organising, it feels younger aside from the established galleries here.

It's the same in Paris. We have kind of the younger, up-and-coming design scene.

We did the Aram show, that's steeped in British design history. Many famous contemporary London-based designers have worked with them at one point or another. It was interesting to see established designers looking at the new vanguards of design and interacting with them and that intergenerational crossover is happening more. All the people that are on the platform, showing London are all very much in dialogue with each other. There's a lot of crossover now, I think we used to not show each other's designs and it felt like you didn't want to muddle things. Now, lots of us have shown the same designers and platformed the same people.