Studio Visit with SKWAT

We visit the former Tokyo Headquarters for creative collective SKWAT, who use the concept of squatting to create community-building creative initiatives using Japan's abandoned buildings

After studying abroad in London, Tokyo-based SKWAT co-founder Keisuke Nakamura noticed the phenomenon of squatting in empty buildings – to live, to create, to set up events. Returning to Japan, a country with an ageing population, cities and villages littered with empty buildings, homes and structures, an idea was born. Starting with an abandoned Laundromat in Tokyo, Keisuke's architecture firm Daikei Mills, in partnership with twelvebooks, launched its first project of what would become the creative collective SKWAT. The squatting philosophy was transformed to work with local companies, landlords and brands to bring new life to empty buildings and build community by challenging the spatial and cultural boundaries in society.

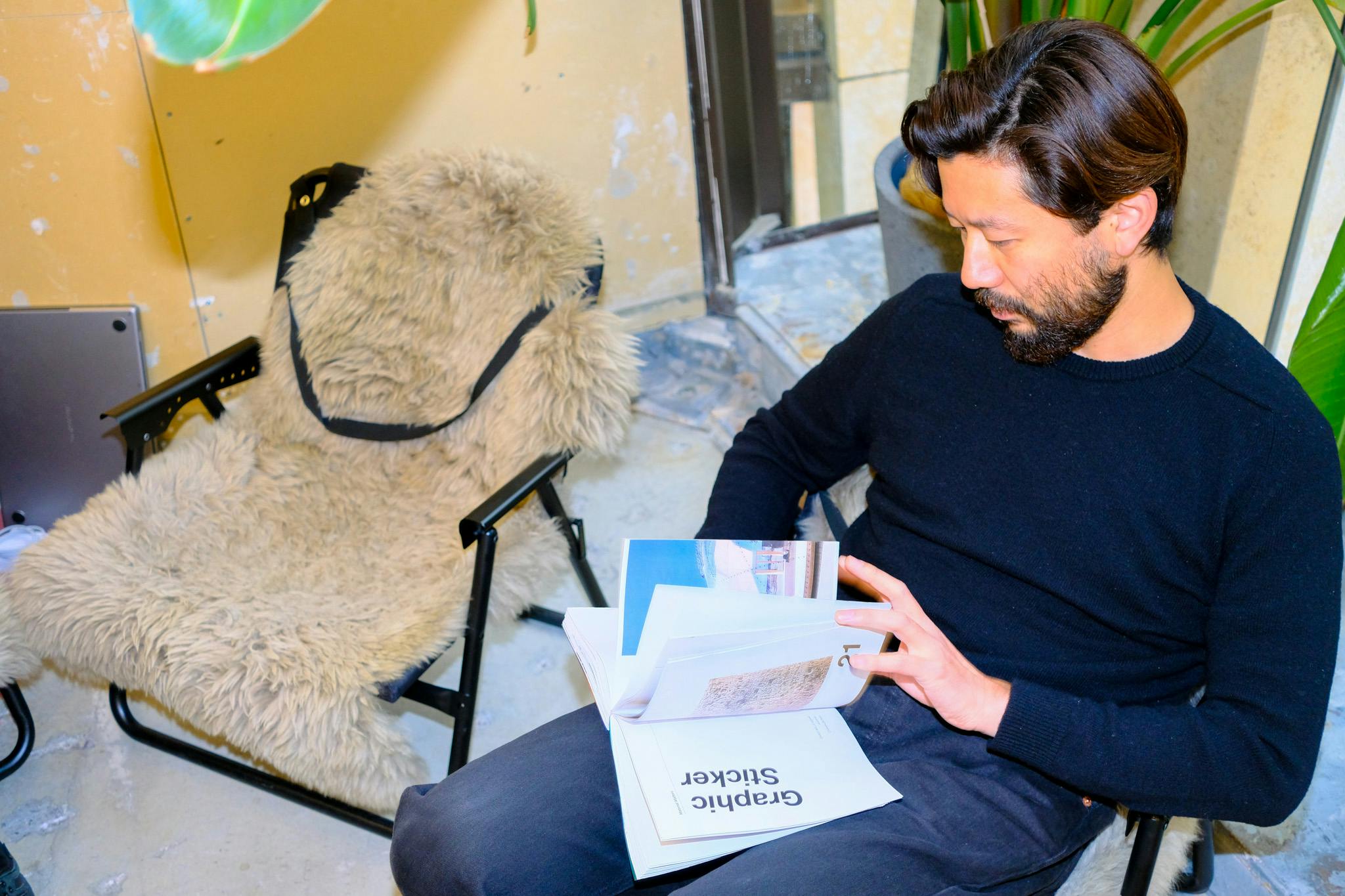

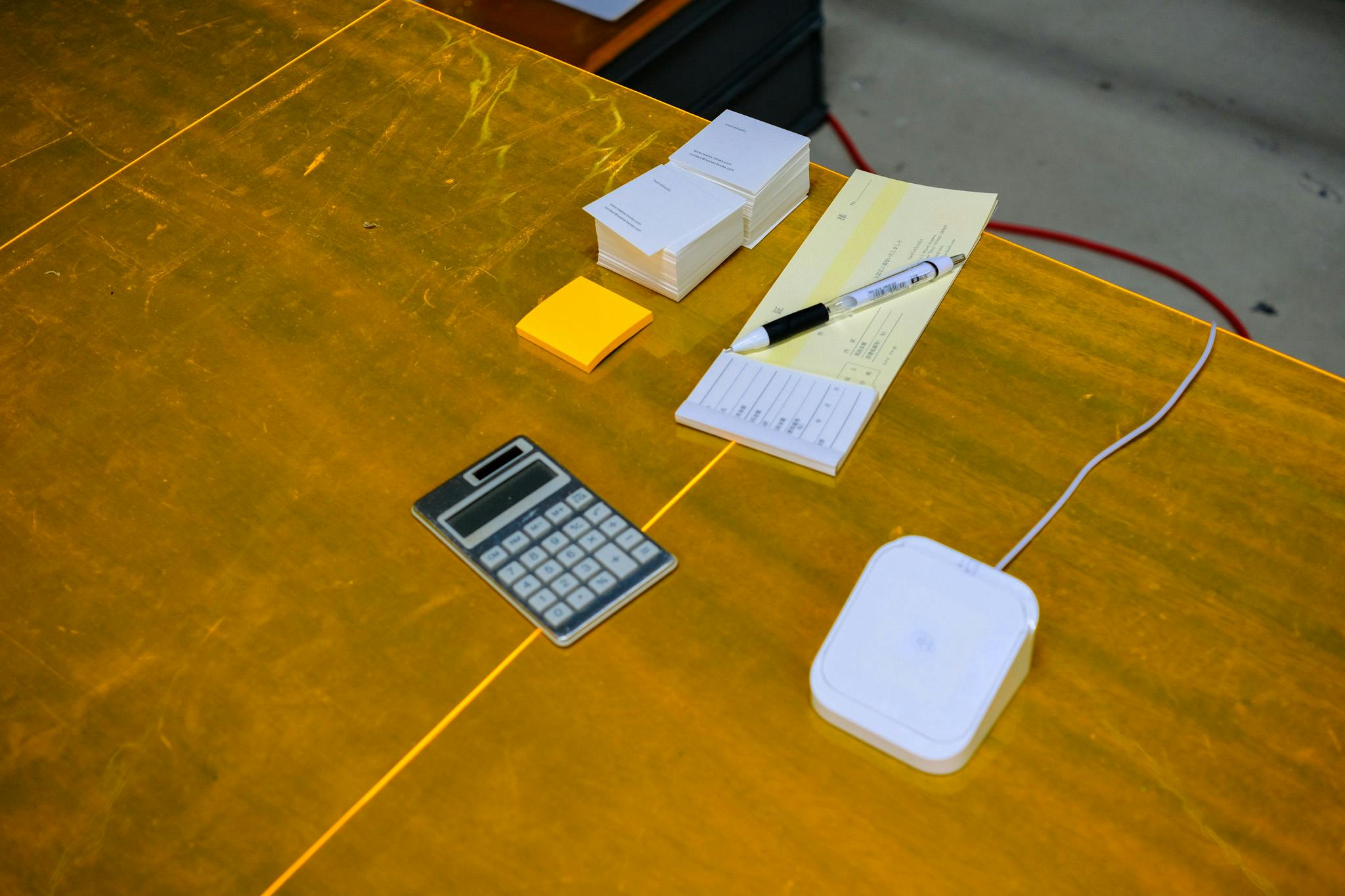

We sat down to chat with a few of SKWAT Collective's members, Keisuke Nakamura, Irene Yamaguchi-Beyer, and Atsushi Hamanaka of twelvebooks, to discuss finding buildings to squat, navigating sustainable approaches to selling damaged goods, funding projects, using material samples to prompt communal creativity.

Keisuke_ I am Kei, the owner of SKWAT and founder of Daikei Mills, which is an architect and interior design office. SKWAT has three core members. We started SKWAT three years ago, and Daikei Mills I started ten years ago.

Irene_ My name is Irene, and I moved here from Berlin just before Covid. I met Atsushi-san and Kei-san who invited me to join SKWAT in 2020 .

Masato_ I am Masato, and I'm measuring Architecture I joined SKWAT two years ago, and I also work at Daikei Mills.

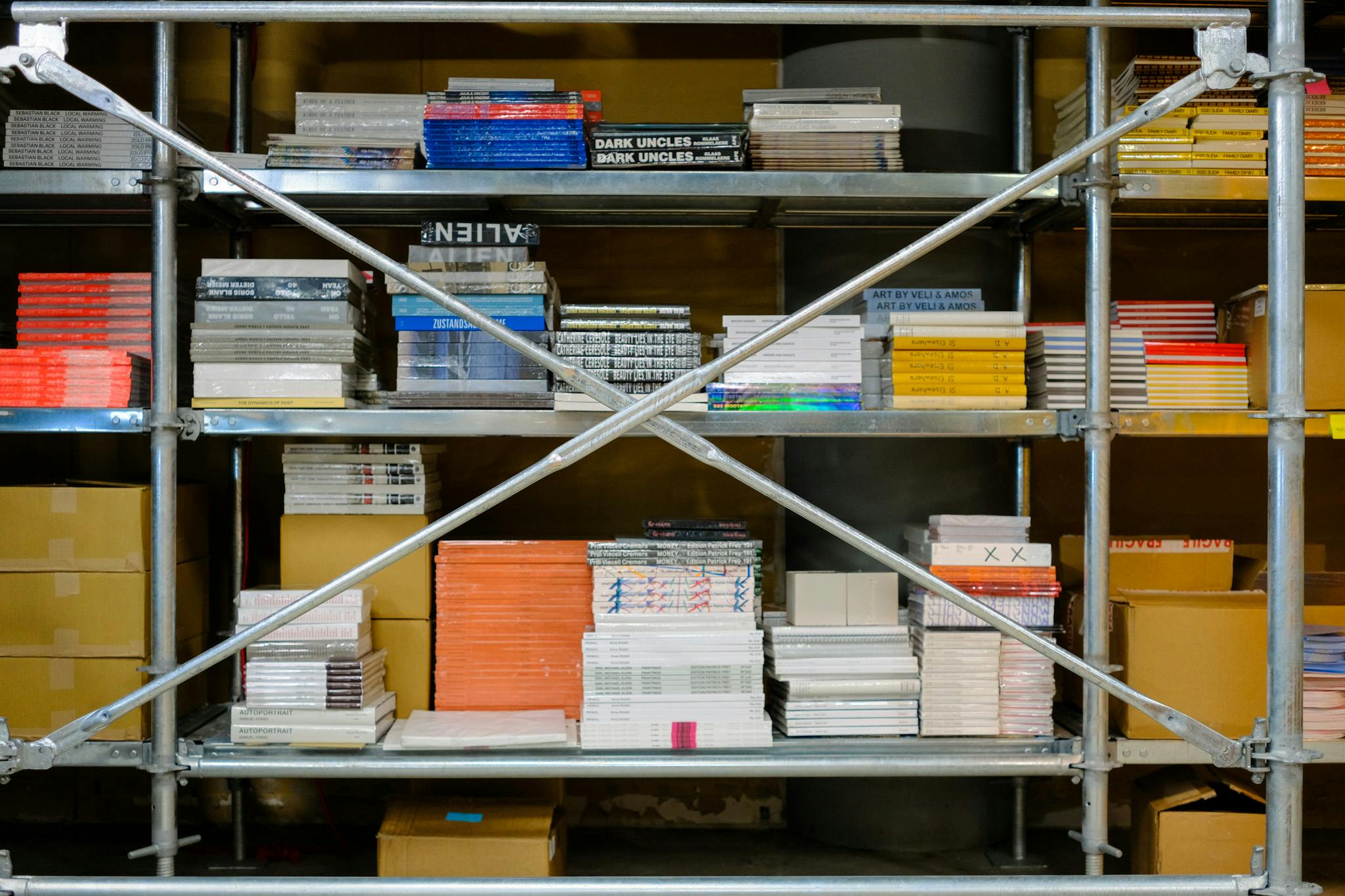

Atsushi_ I am Atsushi, the founder of twelvebooks, which is a company of book distribution mainly for art books. I started it in 2010, and at that time, I met Kei.

Kristen_ So how did all of you come together to create this collective?

Keisuke_ Twenty years ago, actually, we had an alternative space, kind of a free space in Harajuku, which is called “VACANT”. We did things like talk shows, installations, live events, cafes and other things. Atsushi and I worked there together.

Where did you start when you started your studio? How did SKWAT come about, and what type of projects did you do first?

Keisuke_ We mainly started with interior design. Daikei Mills is the client work. So, Daikei Mills is kind of tricky for me. I didn’t want to do interior design for offices; something happened to me as an architect or interior designer.

We primarily began our journey in the field of interior design through Daikei Mills, where our focus has been on client work. However, the role of Daikei Mills posed a unique challenge for me. I found myself looking for something beyond the conventional realm of an interior design studio, something that resonated with me as an architect, interior designer on an artistic level.

I read did you go to school in London, and this is where you first encountered the concept of squatting.

Keisuke_ Yes.

We have a lot in New York and in Berlin as well, but not in Tokyo?

Keisuke_ I have never seen it before. There are lots of abandoned spaces, but none are really used with a kind of creative mindset.

How was that kind of fundamental? How did that inspire you to start SKWAT? And what is the philosophy behind what you do?

Keisuke_ I had a real experience with squatting. When I was younger, I did gigs and a fleamarket or went to some parties with my friends. I remember that kind of experience and feelings, so I was thinking about what could be done as a squat project. I took some images, not visual images but philosophical ones.

You know, squatting has a very political background, and also, there's a certain, I guess, mindset with going a bit of anarchy. So, especially in Tokyo, you can see a lot of very calculated and very clean things, but in squats, there are lots of messy or uncalculated things. That kind of philosophical stuff I took from the images from the point to the SKWAT project.

What type of projects do you do with SKWAT? How did you first start SKWAT? As in, “This is our goal. This is the type of work we want to do.” Or did you just start with a project?

Irene_ The very first project I came across was The Blue Project [VACANT] in Harajuku. It used to be a laundromat. I wasn't working at SKWAT at this point. I joined afterwards when we moved here [to Aoyama]. I was really inspired; it was very different from what I'd seen before in Tokyo because it felt like it was not as regulated. I could feel like some sort of free spirit. Also, the idea of gathering people there based on similar interests I thought it was super interesting. twelvebooks were also selling their damaged books for 1000 yen.

Atsushi_ I basically don't like to do general sales with a 30% discount, for instance. It’s very boring. Kei told me about the SKWAT project and asked me to do something together with them, so after a lot of discussion, I had the idea for Thousand Books. My company is named twelvebooks, so I changed the number simply to 1000. We didn't say it's books "on-sale"; I just said it's "Thousand Books".

This was the impact for the visitors; some people asked, "Why are all of the books one thousand yen?" We explained that twelvebooks was a book distribution company and imported a lot of our stock. A lot of the books arrive damaged, and as Japan is notoriously sensitive to products being in perfect condition - if there is a small damage on the cover or a scratch, people will not buy it. It is a big issue for us as distributors. Thousand Books gave us a way for us to address the issue of the damaged copies and a more creative approach to still being able to sell these to our customers.

Keisuke_ We are always looking for a void in society. And then the issue Atsushi mentioned is a kind of void in the system. So here is a kind of the physical point of a void of space. So, we are all looking for projects within those parameters.

What would you have done with the damaged copies before Thousand Books? Did you just stock them in the backroom?

Atsushi_ We sold them during general sales, but I didn't want to sell like this anymore.

Can you tell me about some projects where you've found a void and how you approached addressing that?

Irene_ It is a lot about opening up spaces to everyone in a sense. We had a project in Kyoto called SKWAT Hertz. We collaborated with the local radio station inside the building. So I think that was another void SKWAT that we discovered, not just in terms of radio, which had some sort of comeback during COVID.

Keisuke_ There was a really interesting story behind the new space in this one particular building. There is a new space designed by Kengo Kuma, but it was kind of dead. Nobody used that space, which is like the atrium area.

Irene_ It was inside a quite established department store. Some department stores are struggling these days; they have seen their best days. So, it was kind of hard to approach a new or younger generation. They tried to change that by extending the department store.

With the new building, a Kengo Kuma built an Atrium, but that didn't help. So we set up a huge concert piano and built a small space for a rest area, and people started to gather around that piano. There was quite a community that started building amongst the locals. This is like a street piano. We didn't advertise at all, nor did we have the support of a PR agency or anything; we just used Instagram.

Irene_ I think interaction is another keyword that describes SKWAT very well. We are always trying to connect with everyone on each project on a different level. At that time, inside of the building which held the department store, there was this local radio station. We collaborated with them as well because we didn't want to squat that void. We wanted to communicate or build something with the local communities that already existed, and then everyone else was interested in participating. So I think that's another big key element of SKWAT.

Keisuke_ We also decided to record the sound of the piano by putting a microphone inside there, recorded 24 hours per day. Also, we did the radio program once a week for three months.

Irene_ We also invited artists to perform small guerrilla performances. They just came and did a little gig using the piano as a tool. So we recorded and also played the recordings of everyone, from people in the community to the artists.

I’m sorry to ask financial questions, but I think it's really interesting who funds that? Do you guys fund it yourself? Do you have a client that pays for it?

Atsushi_ We got offered to be sponsored by Kyocera, which is one of the biggest companies in Kyoto.

Keisuke_ But obviously, we don't always have sponsors. The most important thing is that we don't care about the sponsor that much; just do what we want to do or what we have to do. That's the most important thing. And then the next step is that maybe we could get sponsors for future projects from those who see what we have done before.

Atsushi_ So we always take a risk financially.

Keisuke_ With VACANT, we used to have a lot of underground projects. At the time, we were so young, and it was a very small community, so we didn't have any impact on society. Maybe now we are grown up, and we have to adapt now, we have achieve.

How do you approach sustainability in your projects?

Keisuke_ Surely as a creator, designers and artists we have to think about sustainability. But I don't want it to be the main focus.

In Japan is it more recent that this became a big thing? In Europe, it's been kind of the keyword of the past ten years or so, but then when I went to Korea it was a very kind of new "hot topic". So, how is it in Japan?

Irene_ I mean you cannot compare it to Berlin. I mean, you've lived there. It's been there forever. I think it's kind of a new topic. But then again it's also not that new, I would say it has a different approach.

If you look at the design that SKWAT and Daikei Mills came up with for this space, they are not changing a lot of the original interior or architecture. There is some furniture from other projects from CIBONE and also the LEMAIRE shop downstairs was designed by Daikei Mills and uses beams, the structure of a 100-year-old house. So I think in that sense. It may be a different approach. It's changing. I can feel the change slowly, but definitely, it is coming.

Keisuke_ I think that kind of attitude comes from the real squatting experience because if there is some broken fridge or something in the space you could use it as a desk, for instance, as well. Well, that's a kind of philosophy.

Irene_ Yeah. We try to use what we have already and try to buy as little as possible. We just try to use what we have.

But I really like that because you know I came from fashion. I used to work in fashion production on the runway shows, and I would get really stressed out seeing how they would create these huge sets and then destroy them and throw them all out. We have something in Paris called Les Reserves des Arts, which is a place where you can donate materials and then a young artist can come and buy these second-hand materials for affordable prices, and a lot of the fashion houses refuse to donate materials from their sets. The attitude is that they don't want anybody to use their materials, so they prefer just to destroy them. And it was only used for a fifteen-minute fashion show!

Irene_ There was also another interesting project, Material Matters, which also touched upon the topic of sustainability or repurposing things and materials. A lot of material samples accumulated in the office as references. Normally, at the end of the year in Japan, we have this thing called “Ohsoji”, where the office is cleaned before the new year starts that during that time. All those samples usually are thrown away like nice pieces of beautiful marble. The small samples that you also cannot buy anywhere because they are coming directly from the maker.

We were thinking, what can we do with that? Then we decided to do Material Matters. We showed those samples and also explained to everyone who came what they were used for in the past and how they can be used and transformed. We gave them away for free to everyone who was interested, but we asked everyone a favour in return. It was not a must, but we asked them to share with us what they were planning to do or what they did with the material samples and, if possible, to upload them on Instagram and add a hashtag so we could document and share them with the community.

How do you balance client work and personal projects?

Keisuke_ You know, sometimes we need money to do a project. I don't want to do only small projects. Daikei Mills always does client work, so sometimes I use the money from those projects to support the SKWAT projects, of course. Also, now, if I do a very interesting project with SKWAT, I could get some of the work from the customers of Daikei Mills. So that's a very good circulation as a business side. We are so lucky that very big clients sometimes now, as I said in the Kyoto project and also the Milan project last year, that's sponsored by Uniqlo.

When you approach projects, is there a way to measure impacts?

Irene_ When we find a new place, when we start with the physical space, we often look for a site-specific element and then see how we can han connect with it. For instance, I mean for this place, it was the colour. The red space comes from the red painting's first hanging when we came here. And then, we look into the history of that place. For instance, for the upcoming Kobe project. Now we were looking into Kobe, the neighbourhood, the area – what's already there? What kind of neighbours are there? What kind of communities already exist?

In the end, what makes a successful project for you?

Irene_ When we feel like we could reach out to new people we haven't met before, or we could reach out to people from different backgrounds – that creates some sort of community sense or new synergies. Maybe not an artist collective but more like a movement or initiator trying to change perspectives on a lot of different levels. I think when we get the sense that we could create synergies, the community started to grow around our projects.

I think it's the hardest thing to do in a genuine way and it must be the most rewarding.

Irene_ Yeah. It's really rewarding.

So what's next? What's a dream project you'd love to do?

Keisuke_ We are always thinking about the future project case. We will have to leave this space in April. It's not decided, but we are sixty or seventy percent sure that we need to move from here. We have a lot of abandoned space in Tokyo, but almost all the spaces we've found are not really interesting.

How do you find the owners of an abandoned place?

Keisuke_ One of the places we are moving to is the JR train company, and then we just found out that we won the place.

So you know the was already owned by them.

Irene_ We found it online. So we have the new space that we are hoping to use, which is owned by the big train company JR. Division for that place is more centered around and workshop like an open learning space where we can hopefully also use those material samples. Then, make a reference library with twelvebooks. So, trying to open up a space that is accessible to everyone who is interested. There are not so many open workshops, especially in Tokyo. But on top of that, I think for the next place, the overall vision is also to have some sort of learning space because all the members from SKWAT have very different backgrounds. And I feel like that synergies there are many things everybody can share.

SKWAT is also about a lot about sharing knowledge. Kei is teaching at the university, so he's working a lot with students as well. Atsushi is also working with the educational institutions. So, to bring the world to us, in that sense, is a more practical approach, I would say.