Studio Visit with Grace Prince

We visit the Zurich, Switzerland, studio of British Designer Grace Prince

One late afternoon in 2021, as the sun set over Venice, I returned to the table with my Campari Spritz, joining friend and design editor Laura May Todd. "I met Grace in Milan after we connected over a post you made about her work on say hi to_!" Laura said as she introduced me to designer Grace Prince. It is a special privilege when you get to know a designer and their work at the beginning of their creative journey and career, to be able to witness how their vision unfolds through various mediums, experimentations, themes and bodies of work.

Fast forward to 2024, it's Prince's second solo show in Milan, which stands out as one of the best exhibitions for the second year in a row at the world's most important design event, Milan Design Week. On Via Kramer in Milan, at Grace's sophomore exhibition ‘Attentive Still’, I quietly observe a vase thoughtfully assembled of hammered metal pieces with a silver finish and a bronze integration, born from a collaboration with fellow British-born artist Joanne Burke. Grace's bodies of work have evolved through a romantic and considered approach, touching on both an iteration of minimalism and the whimsical. Focusing on 'gestures' and built tension, she creates inanimate fine objects charged with energy and emotion. She describes these intentional gestures and assemblages as 'Poetic Fragility', which deeply connects these objects with each viewer in their own way.

We discuss the essence of beauty, what that means to her and where she finds it in everyday life. Soft-spoken yet deeply focused and confident – I am curious to understand the creative process of the designer whose work seems to mirror and perfectly embody her strong yet delicate essence. Our conversation bring us everywhere, from her first career opportunities in Milan to working as a researcher for architect and professor Anne Holtrop in Zürich, to the necessity of time and working slowly and her study and experimentation with built-tension and gestures.

Kristen_ Your work explores the juxtapositions between materials, surfaces, and alignment. How do you interrogate yourself, your inspiration and different issues to get to the root of your creativity?

Grace_ It's all about cultivating a style that gets stronger and stronger with time so that you can access it to help you make decisions. My work is making decisions. I'm constantly working with taste and style.

I'm always interested in how people cultivate that because the conversation about copying is so present these days and I feel your work is so unique.

It somehow feels natural. So, I don't know where it came from. Maybe the overarching sensibility of my work is this poetic fragility, which people seem to resonate with. I've had time to think about that. It stems from childhood nostalgia for learning about materials that you’re touching, exploring them for the first time and breaking them. There's a lot of enjoyment in breaking. There is this poetic sense about hard/soft juxtapositions. The way things are held and an exploration of texture, form and materials put together.

I like that people don't fully understand why they like it. They just know they like it, and so I don't think it should be overly explained. It should just remain like a beauty which can exist for beauty's sake in my opinion.

What have you discovered about yourself through learning about your taste or style? And what does beauty represent for you?

Along with dealing with taste, style, and sensibility, which can't be fully harnessed or accessed, you have to reach a certain tension. You're also dealing with these works being put into a space. So the concept of space becomes extremely relevant. You're constantly going into spaces and analysing or just absorbing them somehow. Space has become very essential and beautiful to me. That doesn't have to mean expensive. It just means it can be raw. My floor at home is completely ruined and I love the open wood. You can see all the scrapes or the marks. I like this rawness, it speaks to the overarching concept of beauty. It's not just about one object or one space, it's about a curation of a space, of pieces together inside the work and in the space that it's going to inhabit.

You moved to Milan and assisted furniture designer Vincenzo De Cotiis. How did this come about and how did you realise that your interest may have shifted to furniture?

Vincenzo’s an extremely generous person to be assisting. He gave me so much responsibility considering that I had just moved to Milan. I had just graduated and didn't have much experience except for a carpentry apprenticeship. After graduating in fashion design I realised pretty quickly that I wanted to move towards objects and deal with materials rather than fabric. I took over my parent's garage for a bit and started watching YouTube videos before making furniture.

Then I got a job with Vincenzo De Cotiis. They knew from the interview that I was quite naive, but I think they saw something in me and would give me a lot of freedom, trust and responsibility. I was involved in the process of working in the atelier right next to the artisans. I didn't speak Italian so I had to draw on the table. I learned Italian pretty quickly as not many people there spoke English. It was like a baptism of fire. I learned so much and developed my taste in doing so.

How did you learn how to make vases?

On site. I think as you do with anything. This culture of having to study something as the only way to do it is not always the best. I think you learn by doing. I would say leave a bit of naivety in yourself and your practice and not feel you have to learn everything and get too technical because often an unexpected mistake leads to, for example, this 'this defect piece of steam bent wood'. There is a room where the steam bending company leave all the woods they can't sell as something went wrong in the production process, they bent in the wrong way for instance, but I find this truly beautiful and am using it in my new collection. I appreciate the defects in things. I often find the mistakes to be beautiful. Apart from a carpentry apprenticeship and my degree in design, I learned on the go working next to artisans, going to factories and seeing how things work.

I think allowing mistakes to happen is something that we don't talk about enough, but I know a lot of designers feel the same way, many new ideas would never have popped up if something hadn’t gone wrong in the process.

That goes back to your question of ‘how do you cultivate beauty?

Yes indeed.

Your first show in 2022 in Milan, ‘Entropy & Desire’ took the scene by storm. It was the standout emerging design show of the year. Can you tell us a bit about that collection and how your career has evolved since that event?

I never wanted to rush this process because it was a decision to try and see where my work could take me, also doing it the slow way. So, I always had another job on the side financially supporting me, because I never wanted to feel I was under any pressure. Otherwise, work suffers. I wanted the work to develop organically and get it to a good level. Then the Apparatus space arrived through a friend. They were showing in New York that year and wanted to give it to a young designer but the designer cancelled two weeks before. The curator Federica Sala knew of my work and thought this would be the perfect opportunity, in the most perfect location. Damir Doma, who’s also a collector, wandered in by accident because he was early for a meeting at Carwan Gallery. We talked for two hours, and he came back the next day with his aunt who bought a piece.

But you're right, I think it was a surprise for people as I came out of nowhere, but that’s because I never really wanted to push anything before it was ready.

You took the time to give yourself a bit of privacy with your work until you felt it was ready to show.

I was extremely serious and had this self-confidence, but I needed the work to be at the right level.

I think that's an important thing. I mean, especially with this Instagram culture, people have expectations of things arriving fast.

Yeah. Because we're sort of given things fast. But actually, things take time and they should take time.

You’ve stood out to me as a designer with a powerful vision, especially at a time when it’s harder than ever to do so as we are inundated with a constant flow of trends and images.

This fast pace is an issue. They talk about it a lot in the fashion industry. You see the most beautiful collection being presented and then the first question after the show is ‘And what's next?’ I mean, people ask me for pieces with a one-month deadline because the work somehow looks like it's made fast. But it’s slow, building up this sensibility takes a lot of time and sometimes my brain goes into overdrive and it's all about building up this specific tension including in your body so that you can push it into the work.

Phyllida Barlow wrote about chance and talked about the ‘lazy gesture’ during a Shenkman Lecture in Contemporary Art in 2019. Noting that “the lazy gesture” requires an enormous amount of organisation and charge and to get that sense of informal urgency there is precision involved. When things are sort of thrown together, the gesture of chance is something that has to be built up.

It takes a lot of energy to build up the moment for it to happen. I can spend all day building up this tension, staring at a piece and trying different things. And then I feel something's hitting correctly inside me and in the room, so that's actually what takes time for me.

I think it's like a very thoughtful insight and the fact that you recognise it in yourself because I feel like it’s hard to express with words.

Yes, it's really hard to put in words and people don't often get it, which is fine. The two main misunderstandings of my work are that it's made from found pieces and that it’s made quickly. But I like that it has this feel to it. They're not found pieces because I like to dictate my gesture to them and found pieces already have a gesture. And my work is not fast, because I don't think gestures can happen fast. The moment of the gesture is fast, but the buildup of tension towards the gesture is really slow.

We'resortofgiventhingsfast[withInstagramculture].Butactually,thingstaketimeandtheyshouldtaketime.

Grace Prince

Can you tell us a bit about what you've learned traversing the design scene as an independent designer? What do you wish you knew at the beginning and what advice would you give designers that are just starting?

Keep this sense of naivety. Make sure you realise that things don't just happen overnight.

Everyone has a side hustle. I think that's very important so as not to put too much financial pressure on yourself and rush things or make a ton of additions and compromise on materials.

To young designers, it's a tough industry and there's a lot of pressure to succeed and things take time. It’s so important to let things happen organically. This also goes to contacts, friends, and your network. If you're sending something to someone who you hope will like your work and somehow it doesn't work out, it's okay. Don't push too hard. I'm not saying don't push at all because of course you need to push and be serious about it.

It's okay to have your niche, where you're understood and it's okay that you're not understood in another part of the design scene.

Every collaboration I've done has only happened in a very organic way, with either me or them presenting an idea.

Your most recent show Attentive Still in 2023 in Milan presented pieces developed as part of the Numeroventi residency in Florence. What did your residency look like? And how did it help you develop this body of work?

The residency was a great example of an organic relationship because we had been in contact for three years so I was definitely in the right position for it when it arrived.

And Martino and the team were so trusting. I went to an event hosted by my friend Stefanie Barth from the creative agency Frey Barth Studio in Milan. Then the idea of an exhibition arrived and Joanne Burke came on board with this jewellery integration. She came to Numeroventi and worked with the local artisans and this whole dynamic grew into this beautiful show where everybody’s part felt heard.

Many people don't know what to expect from a residency and I guess everyone's different. Did you already have a project in mind?

It depends on how you work. When the time is right, you apply with a project in mind, they look at your work and invite you. But for example, there was a painter who hadn't worked with furniture before and they were very open to exploration.

Once there, they introduce you to different local production techniques. They also have this small workshop/studio with tools to use for your work. But at the end of the day, it's also about being very aware of your site and the incredible artisanal practices surrounding you in Florence. And that was also very important to me especially since I deal a lot with sensation. So it was a lot about getting this mood of Florence, the dark corners in churches with silver leaf elements, which would bring in a hint of light. It was also having a connection with the artisans and people around me.

What was the timeline of that whole experience?

Four weeks altogether, but we didn't want to do it in one bunch because I needed time between to think and reflect.

You also did a residency in Japan last summer. How were the two residencies different and how did each experience influence your work?

The residency in Japan initially lasted three weeks but it was more research-based. My host had a background of working very closely with local artisans in the Kyoto region so it was like a goldmine for me. The places I visited completely transformed the way I work, through learning the mentality of the people and artisanal practices. I was looking through books, going to museums, temples and sites and understanding my surroundings.

My host had many roles and one of them was planting Urushi trees to recultivate the land from a monoculture of cedar and cypress trees. So it was also understanding the source material of Urushi, and then going to this gallery where the Urushi vases were presented.

I wanted this linear understanding from the beginning to the end of a material. That's also what I do at the ETH university with Anne Holtrop. My job is to research materials and it's very important that we look at them from such a broad context, including the cultural heritage, political understanding, production techniques, contemporary usage of it, how artists are using it nowadays and how it was used historically.

You also work in material research at the design studio Material Gesture, under Professor Anne Holtrop. How do you approach researching new materials and what is the process of experimenting with them?

I have more of a support role for students to experiment. I start by presenting my research via a lecture and book to the students to get the ball rolling as they only have three months to make their projects. I do a seminar, we discuss their ideas and put them in contact with artisans.

I also organise a trip for them which is a pivotal moment. We visited a gorge and saw the way the glacier had shaped the rock. We went to a salt mine to see how the water had filtered the earth and left these traces in the mine…it's all about understanding materials from a broad perspective.

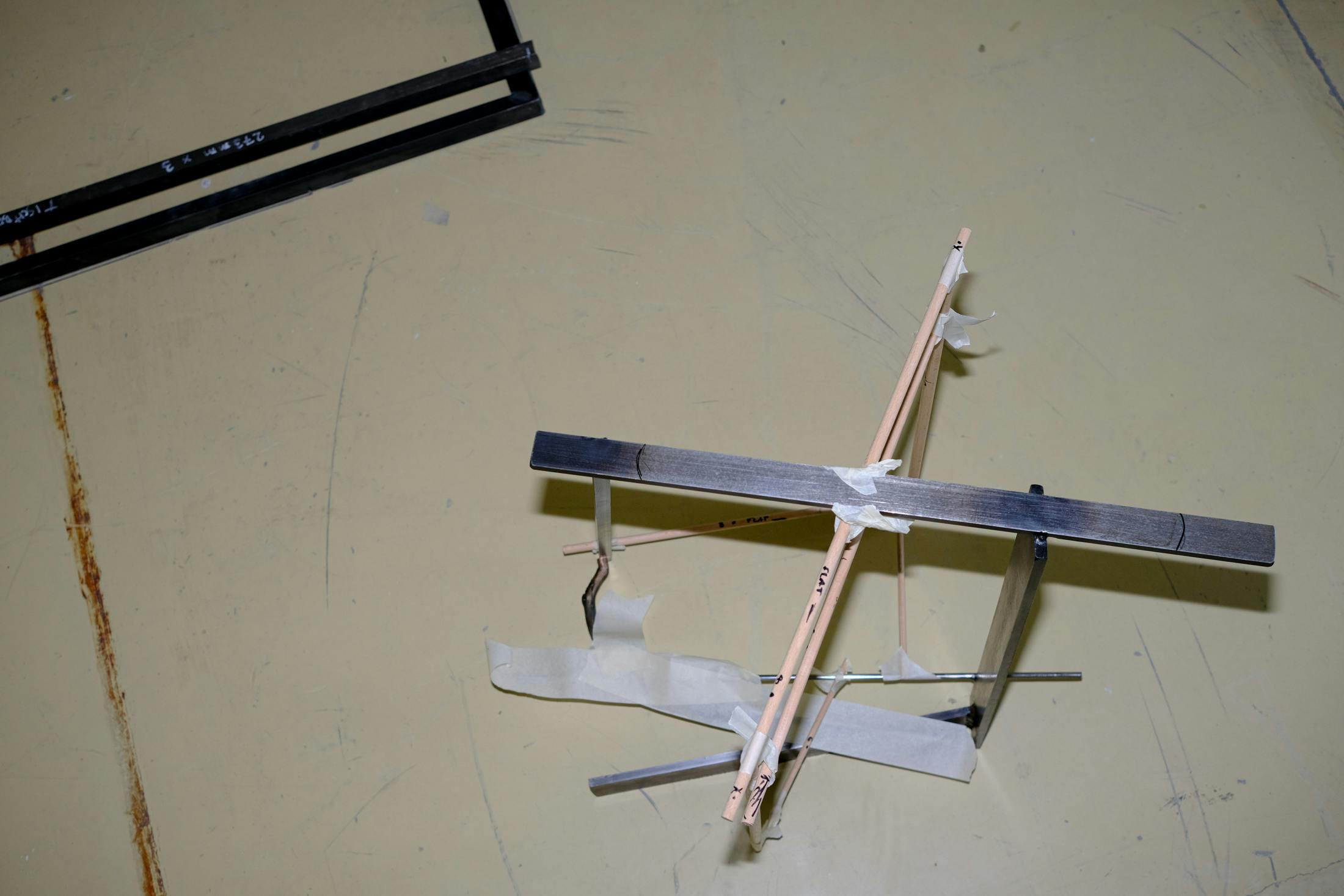

The Material Gesture design studio is extremely experimental. We encourage students to make as much mess as possible, going back to that naivety of just trying things out, not reading the instructions.

You also recently went to India. What did you discover there?

It was a really special trip because we weren't studying one material or a site as we usually do. We were studying heat and how materials are manipulated by heat. India is very unique for this, for example we visited their traditional and contemporary brick kilns.

We were granted access to a lab where they grow diamonds and saw this more recent process where they apply a lot of pressure, heat and gas to a very small speck of carbon, and it expands over days to become a lab-grown diamond. On a molecular level, it’s really the same as a diamond. India is the only place in the world that does this.

We also went to see a particle board manufacturer that was leaving sugarcane husks to dry before pressing them with heat to make particle boards.

What are some of the projects that came out of the research?

My favourite project was a historic cooking room in Switzerland with a fire pit covered in soot. One student took a contemporary approach and simulated how it would be to light a fire for many days in our studio space. He analysed what would be needed to create the right amount of soot and where it would deposit. It was a very technical analysis, involving the possibility of changing the shape of the roof so that the soot would arrive in different textures. It was such a simple yet beautiful idea.

You have a new solo exhibition coming up ‘Held Absence at Béton Brut Gallery. Is this an ongoing exploration of Gestural Assembly or is this a new body of work?

The show was born from the research I carried out during my residency in Japan. I was visiting a carpenter's workshop and I noticed a tree trunk he had attempted to cut with a chainsaw. He said he had made a mistake and just left it there. My assumption was he left it there as a sort of reminder of his mistake. I found it poetic the way it was just hanging there. I went back at the end of my residency and asked if I could have it. I think he was quite happy for me to cut it off, as it was a symbol of embarrassment. I brought it back to Switzerland and I cast it in a silicone mould. That became the starting point of the collection, because the piece itself is like a piece of jewellery with details and edges.

So it's been about accentuating the beauty of this with a simplistic, minimalistic assemblage of the pieces that support it somehow. I do want the work to become cleaner, and more minimal, to push it even further, harnessing the poetics of assemblage, gesture, and being held there. This Held Absence speaks to that because of this attitude of minimalism, not understanding how it's being held.

The sensation is always the starting point, but then it turns into a play of material. It's trial and error and it's about trusting the process of placing a gesture, understanding if that gesture is correct, and most importantly, making it functional, because I'm in the design world, not the art world.

Everything is so considered in your work. What makes you lean towards wanting to have a design practice rather than an art practice?

Delicate gestures are not a new concept, it's been studied in art. I could very easily go in this direction and continue the research that others have started but I think the interest lies in having that sensibility with function so that it's a piece that you can live with, it has a use and I think for me that's just more interesting.

It must be nice seeing how different people see your pieces through their lenses and apply them to their spaces.

Absolutely. One friend had it next to his bed, treating it like his baby, bless him. He would send me pictures occasionally of him curating a beautiful flower arrangement on his table.

What do you do when you feel like you hit a roadblock?

It depends. I am at a level of experience where I know that if I have time on my hands, the solution will eventually come to me. I trust the process, I just need to keep working, to keep sitting there in front of the work.

Is there a dream project you'd love to tackle or have the opportunity to explore in the future?

I think that the work is nice on a small scale because they're like these little jewels that can fit in the space. But I would like to tackle a large-scale installation such as an immersive space or if a fashion store wants a large installation, be it temporary or not. It would be such a challenge for me as well in a good way.